Human Genome Project

The project was a bureaucratic miracle launched by three independent visions rather than a single discovery.

The project was a bureaucratic miracle launched by three independent visions rather than a single discovery.

While we often credit the Human Genome Project (HGP) to the late 20th-century tech boom, its origins were actually a "tortuous" path through US public policy. In the mid-1980s, three scientists—Robert Sinsheimer, Renato Dulbecco, and Charles DeLisi—independently proposed mapping the genome to solve different problems, ranging from cancer research to understanding radiation damage. It was DeLisi’s ability to navigate the Department of Energy’s budget process that finally secured the first $4 million to jumpstart the effort.

By 1990, the project evolved into the world’s largest collaborative biological project, officially led by the NIH and the Department of Energy. It was never just a US endeavor; it required an international consortium (the IHGSC) involving 20 universities and centers across the UK, Japan, France, Germany, and China. This public effort eventually faced a high-stakes "genome race" against the private Celera Corporation, which launched a parallel project in 1998, forcing both groups to accelerate their timelines.

"Completion" was a moving target that took twenty years longer than the initial victory lap.

"Completion" was a moving target that took twenty years longer than the initial victory lap.

The HGP is famous for its 2003 "completion" date, but that declaration was a technical compromise. The original project successfully mapped the euchromatic genome—the 92% of our DNA where most active genes reside. The remaining 8% consisted of highly repetitive, "dark" regions like centromeres and telomeres that were too complex for the era’s "shotgun sequencing" technology to assemble. These gaps remained for nearly two decades.

The true "end-to-end" completion only arrived in the early 2020s. In May 2021, researchers reached a level where only 0.3% of the genome was uncertain, and the final gapless assembly was finished in January 2022. This final stretch was achieved by the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) consortium, which used advanced long-range sequencing to finally decode the Y chromosome and other stubborn regions that the original project had to leave behind.

The reference genome is a synthetic mosaic of humanity, not a single person’s blueprint.

The reference genome is a synthetic mosaic of humanity, not a single person’s blueprint.

A common misconception is that the HGP sequenced the DNA of one specific individual. In reality, the "human genome" is a composite scaffold. Because any two humans share about 99.9% of their DNA, researchers sequenced samples from a small group of anonymous donors of diverse ancestries (African, European, and East Asian) and stitched them together into a "mosaic" sequence. This created a universal reference point rather than a biography of one person.

This mosaic serves as a "haploid" reference—a single set of the 23 human chromosomes. Its primary utility isn't in showing us what we are, but in providing a baseline to identify what makes us different. By comparing an individual’s DNA to this master scaffold, doctors can identify specific mutations linked to cancers, rare diseases, and even how a patient might react to a specific medication.

Success relied on "bacterial factories" to clone and sequence billions of fragments.

Success relied on "bacterial factories" to clone and sequence billions of fragments.

To sequence 3.1 billion base pairs, scientists had to adopt a "divide and conquer" strategy. They broke the genome into manageable chunks of about 150,000 base pairs. These fragments were then inserted into "Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes" (BACs)—genetically engineered bacteria that acted as living Xerox machines, replicating the human DNA fragments as they divided.

Once enough copies were made, these fragments were further shattered into tiny "shotgun" pieces to be read by sequencing machines and then reassembled like a massive 3-billion-piece jigsaw puzzle. This process eventually gave way to more advanced methods like RNA-seq, which allowed scientists to measure gene activity directly by sequencing messenger RNA. This technical evolution turned biology into a data science, where the speed of sequencing now follows a "Moore’s Law" trajectory—dropping from a 13-year project to a process that can now be done in hours.

Findings revealed that humans have surprisingly few genes but immense structural complexity.

Findings revealed that humans have surprisingly few genes but immense structural complexity.

One of the HGP’s most humbling discoveries was the gene count. Before the project, many scientists estimated humans would have 100,000 genes to account for our complexity. The final count was much lower—approximately 22,300 protein-coding genes, roughly the same number as a common mouse. This revealed that human complexity doesn't come from having more parts, but from how those parts are used and combined.

The project also highlighted that the genome is much "messier" than expected. It is filled with segmental duplications—nearly identical sections of DNA that repeat over and over. Furthermore, researchers found that over 90% of our genes use "alternative splicing," meaning a single gene can produce multiple different protein products depending on how its sequences are combined. This shifted the focus of genetics from simply "finding the gene" to understanding the intricate regulatory network that controls them.

Image from Wikipedia

The first printout of the human genome to be presented as a series of books, displayed at the Wellcome Collection, London

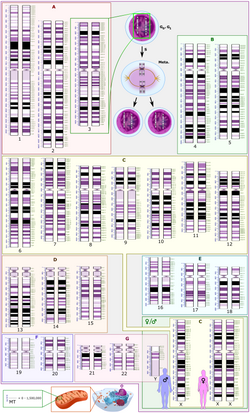

Schematic karyogram of a human, showing an overview of the human genome, with 22 homologous chromosomes, both the female (XX) and male (XY) versions of the sex chromosome (bottom right), as well as the mitochondrial genome (to scale at bottom left). The blue scale to the left of each chromosome pair (and the mitochondrial genome) shows its length in terms of millions of DNA base pairs.Further information: Karyotype

Image from Wikipedia