Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The Manhattan Project raced to produce two radically different physics experiments for immediate combat use.

The Manhattan Project raced to produce two radically different physics experiments for immediate combat use.

The weapons dropped in August 1945 were not identical. "Little Boy," dropped on Hiroshima, was a gun-type uranium bomb so simple in design that it wasn't even tested before use. "Fat Man," dropped on Nagasaki, was a complex plutonium-core implosion device, a technology so temperamental it required the Trinity test in New Mexico to ensure it would actually detonate.

This technical divergence illustrates the sheer speed of development. The United States didn't just build a bomb; it built two distinct supply chains and engineering philosophies simultaneously. By the time of the bombings, the U.S. had moved from theoretical physics to industrial-scale mass destruction in under four years, creating a stockpile that, while small, represented a total monopoly on ultimate power.

American planners prioritized "psychological impact" over military necessity when selecting target cities.

American planners prioritized "psychological impact" over military necessity when selecting target cities.

The Target Committee in Washington specifically sought out cities that had been "left untouched" by conventional firebombing. This wasn't for mercy, but for measurement: they wanted to see the pristine effects of a single atomic blast on urban structures and civilian morale. Hiroshima was chosen for its size and layout, which allowed the surrounding hills to "focus" the blast, maximizing destruction.

Nagasaki was actually the secondary target for the second mission; the primary city, Kokura, was spared only by heavy cloud cover and smoke from nearby conventional raids. This selection process treated entire metropolitan areas as lab specimens, aiming to create a "spectacle of destruction" so undeniable that the Japanese High Command would be forced to abandon their "Ketsugo" strategy of fighting to the last citizen.

The immediate devastation was followed by a medical mystery that transformed survivors into "Hibakusha."

The immediate devastation was followed by a medical mystery that transformed survivors into "Hibakusha."

At the hypocenters, temperatures reached several million degrees Celsius, vaporizing people instantly and leaving only "atomic shadows" on stone walls. Those further out suffered from "flash burns" where the dark patterns of their clothing were seared into their skin. However, the true horror was the "black rain"—radioactive fallout that poisoned those who survived the initial blast, leading to a then-unknown sickness of hair loss, internal bleeding, and organ failure.

The survivors, known as Hibakusha, became a new, marginalized social class in Japan. They faced intense discrimination in marriage and employment due to fears of radiation "contagion" or genetic defects. Their lived experience shifted the narrative of the bombings from a military triumph to a humanitarian catastrophe, eventually fueling the global anti-nuclear movement.

The Japanese surrender was a dual-shock caused by nuclear fire and the sudden collapse of the Soviet-Japanese neutrality pact.

The Japanese surrender was a dual-shock caused by nuclear fire and the sudden collapse of the Soviet-Japanese neutrality pact.

While the atomic bombs provided the Emperor with a "face-saving" excuse to end the war, many historians argue the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on August 9 was equally decisive. Japan had hoped the Soviet Union would act as a neutral mediator for a negotiated peace; when the Red Army instead decimated Japanese forces in China, the "peace party" in Tokyo realized that total annihilation was coming from both the East and the West.

The surrender was not a foregone conclusion even after the second bomb. The Japanese military council was deadlocked 3-3 on whether to continue the war. It required the unprecedented personal intervention of Emperor Hirohito to "endure the unendurable." His surrender broadcast never actually used the word "surrender," instead citing the "new and most cruel bomb" as the reason for ceasing hostilities.

These bombings birthed the "Nuclear Taboo," fundamentally altering the nature of global power.

These bombings birthed the "Nuclear Taboo," fundamentally altering the nature of global power.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only instances of nuclear weapons used in conflict, creating a psychological threshold that has held for nearly 80 years. This "taboo" transformed nuclear weapons from "just another tool of war" into "weapons of last resort." The sheer scale of the civilian suffering in 1945 convinced subsequent leaders that a nuclear exchange could have no winner.

The legacy of the bombings is a paradox: they are credited by some with preventing a bloody invasion of the Japanese mainland and saving millions of lives, while others condemn them as unnecessary war crimes against non-combatants. This tension continues to define the modern world, where the memory of two cities' destruction serves as the primary deterrent against a Third World War.

Two aerial photos of atomic bomb mushroom clouds, over two Japanese cities in 1945

Situation of the Pacific War on 1 August 1945 White and green: Areas controlled by Japan Red: Areas controlled by the Allies Gray: Areas controlled by the Soviet Union (neutral)

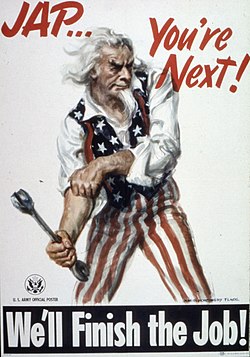

U.S. Army propaganda poster depicting Uncle Sam preparing the public for the invasion of Japan after the end of the war with Germany and Italy

A B-29 over Osaka on 1 June 1945

The Operation Meetinghouse firebombing of Tokyo on the night of 9–10 March 1945, was the single deadliest air raid in history, with a greater area of fire damage and loss of life than either of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

Leslie Groves, Manhattan Project director, with a map of the Far East

The "Tinian Joint Chiefs": Captain William S. Parsons (left), Rear Admiral William R. Purnell (center), and Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell (right)

The mission runs of 6 and 9 August, with Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Kokura (the original target for 9 August) displayed

Various leaflets were dropped on Japan listing cities targeted for destruction by firebombing. The other side stated that other cities may be attacked.

General Thomas Handy's order to General Carl Spaatz ordering the dropping of the atomic bombs

The Enola Gay dropped the "Little Boy" atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Paul Tibbets (center in photograph) can be seen with seven members of the ground crew.

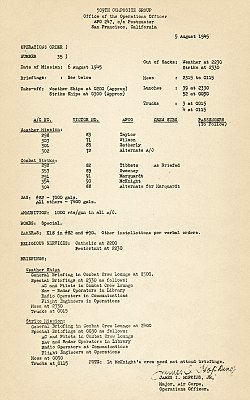

Strike order for the Hiroshima bombing as posted on 5 August 1945

The Hiroshima atom bomb cloud 2–5 minutes after detonation

Ruins of Hiroshima

A burned out domed building surrounded by rubble