Uncertainty principle

Reality has a built-in "resolution limit" that prevents us from knowing a particle's position and speed simultaneously.

Reality has a built-in "resolution limit" that prevents us from knowing a particle's position and speed simultaneously.

The uncertainty principle states that there is a fundamental limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties, such as position and momentum, can be known. The more accurately you pin down where a particle is, the less you can know about where it is going. This isn't a failure of our technology; it is a fundamental constraint of the universe.

This trade-off is expressed mathematically: the product of the uncertainties of these two measurements must be at least half of the reduced Planck constant. In our macroscopic world, this constant is so small it’s invisible, but at the scale of atoms, it creates a "fuzziness" that makes the precise trajectories we see in a game of billiards impossible.

Uncertainty is an inherent property of wave-like systems, not a flaw in our measuring equipment.

Uncertainty is an inherent property of wave-like systems, not a flaw in our measuring equipment.

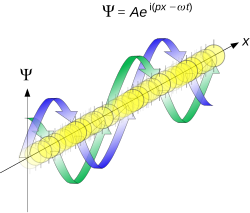

While often explained as a "disturbance" caused by the act of measuring, the principle actually arises from the fact that all quantum objects behave like waves. To describe a particle's location perfectly, you need a wave that is highly localized—a sharp "spike." However, a spike is composed of many different wavelengths added together. Since wavelength determines momentum, a sharp position requires a massive spread of possible momenta.

Conversely, a wave with a single, clear frequency (and thus a precise momentum) must stretch out infinitely through space. You can have a "where" or you can have a "how fast," but the math of wave mechanics—specifically Fourier transforms—forbids you from having both with perfect clarity at the same time.

The principle provides the structural scaffolding that keeps atoms from collapsing and allows matter to exist.

The principle provides the structural scaffolding that keeps atoms from collapsing and allows matter to exist.

If the uncertainty principle didn't exist, atoms would be unstable. In a classical "solar system" model of an atom, an electron would eventually lose energy and spiral into the nucleus. However, the uncertainty principle prevents this: if an electron were confined to the tiny volume of the nucleus, its position uncertainty would be so small that its momentum uncertainty would become enormous.

This high momentum would give the electron enough "kick" to fly away from the nucleus. The "cloud" of an atom is actually the equilibrium point where the electron is as close to the nucleus as it can get before the uncertainty principle forces it to move too fast to stay there. This "fuzziness" is why solid objects feel solid and don't simply collapse into themselves.

Werner Heisenberg’s discovery shattered the "clockwork universe" and replaced absolute certainty with statistical probability.

Werner Heisenberg’s discovery shattered the "clockwork universe" and replaced absolute certainty with statistical probability.

Before 1927, the prevailing "Laplacian" view of physics suggested that if you knew the position and velocity of every particle in the universe, you could calculate the entire past and future. Heisenberg proved this is impossible even in theory because the starting data can never be collected. The universe is not a machine following a single, predetermined track.

This shift changed physics from a study of "what will happen" to "what is likely to happen." While we cannot predict the path of a single electron, we can predict the behavior of a billion electrons with incredible accuracy using probability. This transition from individual certainty to collective probability is what Albert Einstein famously resisted when he claimed "God does not play dice."

The "Observer Effect" is frequently confused with the Uncertainty Principle, but they are distinct phenomena.

The "Observer Effect" is frequently confused with the Uncertainty Principle, but they are distinct phenomena.

In popular culture, the uncertainty principle is often described as the "observer effect"—the idea that hitting a particle with a photon to "see" it knocks it off course. While it is true that measurement often disturbs a system, Heisenberg’s principle holds true even if the measurement is done perfectly without any physical contact.

The observer effect is a logistical hurdle of measurement; the uncertainty principle is a fundamental law of nature. Even in a vacuum with no one watching, a particle does not possess a definite position and momentum at the same time. The "blurriness" is baked into the fabric of the vacuum itself.

Canonical commutation rule for position q and momentum p variables of a particle, 1927. pq − qp = h/(2πi). Uncertainty principle of Heisenberg, 1927.

Position x and momentum p wavefunctions corresponding to quantum particles. The colour opacity of the particles corresponds to the probability density of finding the particle with position x or momentum component p. Top: If wavelength λ is unknown, so are momentum p, wave-vector k and energy E (de Broglie relations). As the particle is more localized in position space, Δx is smaller than for Δpx. Bottom: If λ is known, so are p, k, and E. As the particle is more localized in momentum space, Δp is smaller than for Δx.

Plane wave

Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr

Heisenberg's gamma-ray microscope for locating an electron (shown in blue). The incoming gamma ray (shown in green) is scattered by the electron up into the microscope's aperture angle θ. The scattered gamma-ray is shown in red. Classical optics shows that the electron position can be resolved only up to an uncertainty Δx that depends on θ and the wavelength λ of the incoming light.