Hannah Arendt

Arendt’s precocity was defined by a fierce intellectual independence and a rejection of traditional moral "givens."

Arendt’s precocity was defined by a fierce intellectual independence and a rejection of traditional moral "givens."

Born into a secular, progressive Jewish family in Königsberg, Arendt was raised on "Goethean lines," where education (Bildung) was viewed as the conscious formation of the soul. Her mother, a Social Democrat, encouraged a "normale Entwicklung" (normal development) that was anything but typical; by age 14, Arendt had already mastered Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and Kierkegaard. This early immersion in Greek and German philosophy created a mind that felt at home in the classics but restless in the classroom.

Her independence was literal: at 15, she was expelled from the Luise-Schule for leading a boycott against a teacher who insulted her. This streak of rebellion was paired with a profound sense of "alienation" (Fremdheit), a theme she explored in her only autobiographical essay, Die Schatten. She navigated a world where she was "Germanized" but lacked full citizenship, identifying deeply with the 18th-century socialite Rahel Varnhagen, who struggled with the impossibility of total Jewish assimilation.

She viewed "thinking" not as a quiet academic pursuit, but as a passionate, vital activity fueled by a controversial mentor.

She viewed "thinking" not as a quiet academic pursuit, but as a passionate, vital activity fueled by a controversial mentor.

Arendt’s intellectual life was irrevocably shaped by her time at the University of Marburg under Martin Heidegger. She described him as the "hidden king" of thinking, a man who taught that "thinking" and "aliveness" were inseparable. Their secret romantic affair, which began when she was 18 and he was 35, remained one of the most scrutinized aspects of her life, particularly after Heidegger’s later support for the Nazi Party.

Despite the personal and political fallout, the Heideggerian concept of "passionate thinking" remained her North Star. She later moved to the University of Heidelberg to complete her doctorate on the concept of love in Saint Augustine under Karl Jaspers. This pedigree of existentialist and phenomenological training allowed her to treat political events not as abstract data points, but as urgent philosophical crises that demanded a new vocabulary.

Her philosophy was forged in the "alienation" of statelessness and the physical escape from Nazi-occupied Europe.

Her philosophy was forged in the "alienation" of statelessness and the physical escape from Nazi-occupied Europe.

Arendt’s transition from a scholar of Saint Augustine to a theorist of totalitarianism was forced by the Gestapo. In 1933, she was briefly imprisoned for researching antisemitism. Upon release, she fled to Paris, where she spent years assisting young Jews in emigrating to Palestine. Her experience as an "alien" became literal when the French government detained her in an internment camp following the German invasion.

She eventually escaped to the United States in 1941, arriving with no country and no reputation. Her decade as a stateless refugee informed her later insistence that the "right to have rights" is the fundamental prerequisite of political existence. It was only with the 1951 publication of The Origins of Totalitarianism that she emerged as a major intellectual force, having spent years analyzing how the breakdown of the nation-state allowed for unprecedented forms of state terror.

Her report on the trial of Adolf Eichmann redefined evil as a bureaucratic lack of thought rather than a monstrous intent.

Her report on the trial of Adolf Eichmann redefined evil as a bureaucratic lack of thought rather than a monstrous intent.

In 1961, Arendt traveled to Jerusalem to cover the trial of Nazi lieutenant colonel Adolf Eichmann for The New Yorker. Her resulting book, Eichmann in Jerusalem, introduced the phrase "the banality of evil," sparking a firestorm that would last for decades. She argued that Eichmann was not a demonic villain but a "joiner"—a man who committed horrific crimes because he lacked the imagination and the "thinking" capacity to realize what he was doing.

This conclusion was met with intense hostility; critics accused her of writing an apologia for the Holocaust and of being insensitive to the victims. Arendt, however, remained steadfast in her belief that the greatest danger to humanity was not radical wickedness, but the "thoughtlessness" that allows ordinary people to become cogs in a murderous machine. This controversy cemented her legacy as a thinker who refused to provide easy moral comforts.

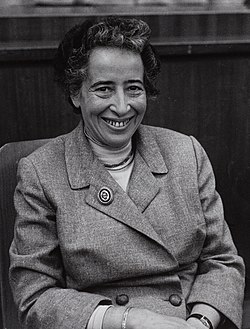

Photograph of Arendt smiling

Paul Arendt c. 1900

Hannah Arendt with her grandfather, Max, in 1907

Martin Beerwald, Hannah and her mother, 1923

Hufen-Oberlyzeum c. 1923

Hannah Arendt's birthplace in Linden

Berlin University

Hannah, 1924

Martin Heidegger

Hannah Arendt (2nd from right), Benno von Wiese (far right), Hugo Friedrich (2nd from left) and friend at Heidelberg University 1928

Günther Stern and Hannah Arendt in 1929

Memorial at Opitzstraße 6

Prussian State Library 1939

Arendt in 1933

Memorial at Camp Gurs