Green Revolution

The revolution replaced traditional farming with a "package" of industrial inputs designed for maximum caloric output.

The revolution replaced traditional farming with a "package" of industrial inputs designed for maximum caloric output.

The core of the Green Revolution wasn't just better seeds, but a total technological shift. Farmers moved away from traditional methods toward a synchronized system of high-yielding varieties (HYV) of wheat and rice, massive applications of chemical fertilizers, and synthetic pesticides. These new "miracle" seeds were bred specifically to respond to intensive nitrogen inputs and required controlled irrigation to thrive, making water management infrastructure a prerequisite for success.

This transition was often enforced through "policy packages." Developing nations were frequently granted loans on the condition that they modernize their agricultural sectors—privatizing fertilizer distribution and moving toward large-scale mechanization. This shifted the farm from a self-contained biological system to an industrial enterprise dependent on external global supply chains and credit.

Born in Mexico, the movement was a geopolitical strategy to prevent "Red" communist revolutions through food security.

Born in Mexico, the movement was a geopolitical strategy to prevent "Red" communist revolutions through food security.

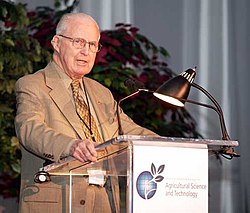

The term "Green Revolution" was coined in 1968 by USAID's William Gaud to explicitly contrast it with the "Red Revolution" of the Soviets. The logic was simple: hungry people are more likely to turn to radical politics. The movement began in the 1940s when U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace, appalled by meager corn yields in Mexico, persuaded the Rockefeller Foundation to fund a research station. Led by Norman Borlaug, this project transformed Mexico from a wheat importer to a self-sufficient exporter in just 13 years.

Mexico served as the global laboratory for this model. The success of these agricultural stations—which later became the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT)—showed the Cold War-era West that technology and capital could stabilize volatile regions. By increasing the number of calories available per person, governments hoped to relieve the social pressure for radical land redistribution.

"Miracle Rice" and hybrid wheat saved over a billion people from starvation across Asia.

"Miracle Rice" and hybrid wheat saved over a billion people from starvation across Asia.

In the 1960s, India and the Philippines faced catastrophic food shortages. Agricultural scientist Norman Borlaug introduced semi-dwarf wheat to India, which produced yields ten times higher than traditional varieties. Simultaneously, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines developed "IR8" rice. This "Miracle Rice" produced five tons per hectare without fertilizer and up to ten tons under optimal conditions, effectively decoupling population growth from immediate famine.

While Borlaug is the Western face of the movement, China’s "father of hybrid rice," Yuan Longping, achieved similar feats independently. His work on hybridizing wild rice strains allowed China to feed its massive population despite having limited cultivable land. Between 1979 and 2014, China’s poverty-stricken population plummeted from 490 million to 82 million, largely credited to these breakthroughs in food security.

Success required more than just seeds; it demanded radical chemical alteration of the environment.

Success required more than just seeds; it demanded radical chemical alteration of the environment.

The Green Revolution often succeeded by forcing the environment to adapt to the plant, rather than the other way around. In Brazil, the vast Cerrado region was once considered "unfit for farming" due to its acidic, nutrient-poor soil. To fix this, farmers poured millions of tons of pulverized limestone (lime) onto the fields to neutralize acidity. This decades-long chemistry project turned Brazil into the world’s second-largest soybean exporter and a global powerhouse in beef and poultry production.

However, this environmental engineering came with a high price. The intensive use of groundwater for irrigation has depleted major aquifers, particularly in China and India. Furthermore, the heavy reliance on nitrogen-based fertilizers has significantly increased greenhouse gas emissions and contaminated local waterways, leading to a "burial ground" of ecological health in the very places where the revolution was born.

The model has struggled to take root in Africa due to a lack of infrastructure and high ecological diversity.

The model has struggled to take root in Africa due to a lack of infrastructure and high ecological diversity.

Despite repeated attempts to export the Mexican and Indian models to Africa, the Green Revolution has seen limited success on the continent. Critics and researchers point to a "general lack of will" from local governments, but the challenges are also physical. Unlike the vast, uniform plains of the Punjab or the Cerrado, many African regions feature high diversity in soil types and slopes within small areas, making a "one-size-fits-all" seed and chemical package ineffective.

The failure in Africa highlights the socio-economic divide created by the revolution. Because the "package" requires expensive seeds, machinery, and chemicals, it often benefits wealthy landowners who have access to credit. In the Philippines and elsewhere, this led to a debt cycle for poor farmers, proving that while the Green Revolution solved the problem of producing food, it did not necessarily solve the problem of access to it.

After World War II, newly implemented agricultural technologies, including pesticides and fertilizers as well as new breeds of high yield crops, greatly increased food production in certain regions of the Global South.

Locations of Norman Borlaug's research stations in the Yaqui Valley and Chapingo.

Norman Borlaug is called the "Father of the Green Revolution" for his work developing high-yield, disease-resistant wheat varieties that significantly increased global food production and helped avert widespread famine.

Wheat yields in least developed countries since 1961, in kilograms per hectare.

World population 1950–2010

World population supported with and without synthetic nitrogen fertilizers.

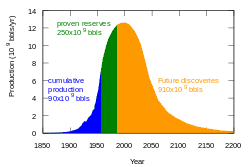

M. King Hubbert's prediction of world petroleum production rates (1968 peak of USA, 2005 World conventional oil peak, 2018 all liquides including corn to oil peak). Modern agriculture is largely reliant on petroleum energy.

Increased use of irrigation played a major role in the green revolution.