Gothic art

Gothic art emerged not as a standalone movement, but as a secondary evolution driven by the "pointed" revolution in French architecture.

Gothic art emerged not as a standalone movement, but as a secondary evolution driven by the "pointed" revolution in French architecture.

The style was born in the early 12th century at the Abbey Church of St Denis in France. Unlike most art movements where painting leads the way, Gothic art followed the lead of architects. The transition from the heavy, rounded Romanesque style was slow and uneven; while buildings adopted pointed arches and flying buttresses almost immediately, the "Gothic" style of figures in painting and sculpture took another 50 years to catch up.

This lag created a unique period of overlap where traditional, stiff Romanesque figures were often placed inside cutting-edge Gothic structures. It wasn't until around 1200 in England and France—and much later in Italy—that figures began to "loosen up," becoming more animated in their facial expressions and moving more freely within their pictorial space.

The name "Gothic" was originally a Renaissance slur intended to dismiss medieval creativity as "monstrous and barbarian."

The name "Gothic" was originally a Renaissance slur intended to dismiss medieval creativity as "monstrous and barbarian."

During the 16th century, Italian writers like Giorgio Vasari and the painter Raphael used the term "Gothic" pejoratively. They believed that the Sack of Rome by Goth tribes in 410 AD had destroyed the "correct" classical proportions of the ancient world. To them, the pointed arches and ornate details of the Middle Ages were a "monstrous disorder" that lacked the grace of Greek and Roman aesthetics.

Ironically, the people who actually created "Gothic" art called it Opus Francigenum ("French work"). It took centuries for the term to lose its negative connotation. By the time of the German Romantic movement, the "barbaric" label was reclaimed as a point of pride, with thinkers reimagining the style’s intricate patterns as an echo of primeval German forests rather than a failure of classical logic.

A theological shift toward "humanity" transformed distant Byzantine icons into affectionate mothers and suffering mortals.

A theological shift toward "humanity" transformed distant Byzantine icons into affectionate mothers and suffering mortals.

One of the most profound changes in Gothic art was the humanization of religious figures. In the preceding Byzantine style, the Virgin Mary was depicted as a rigid, hieratic queen. Gothic artists reimagined her as a "well-born aristocratic lady," often shown cuddling her infant, swaying her hip naturally, and showing maternal affection. This reflected a broader resurgence in Marian devotion that prioritized intimacy over awe.

This trend toward realism extended to depictions of Christ. Influenced by movements like the Devotio Moderna, artists began to emphasize his human vulnerability. The "Man of Sorrows" and the Pietà became popular subjects, showing a wounded, suffering Christ intended to evoke empathy from the viewer. Even in scenes of the Last Judgment, Christ began to be shown exposing his wounds to the audience, bridging the gap between the divine and the human experience.

The rise of a wealthy middle class broke the Church’s monopoly, creating a boom in secular art and personal "pocket" bibles.

The rise of a wealthy middle class broke the Church’s monopoly, creating a boom in secular art and personal "pocket" bibles.

As trade increased and cities grew, a new bourgeois class emerged with the money to patronize the arts. This shifted the focus away from massive cathedral commissions toward smaller, personal works. The "Book of Hours"—a private prayer book—became a medieval bestseller. These were often lavishly illustrated with "drolleries" (humorous margin sketches) and scenes of daily life, reflecting the tastes of the laypeople who bought them.

This era also saw the professionalization of art. Artists moved out of monasteries and into urban trade guilds. For the first time, we see a significant increase in artists signing their names to their work, signaling a move from the anonymous "craftsman" to the recognized "individual artist." This period produced the first "International Gothic" style—a sophisticated, courtly aesthetic that linked the elite classes of Europe before the Renaissance took hold.

While Southern Europe stayed loyal to church frescos, Northern Europe pioneered stained glass and the "micro-realism" of oil painting.

While Southern Europe stayed loyal to church frescos, Northern Europe pioneered stained glass and the "micro-realism" of oil painting.

Geography dictated the medium. In Italy and Southern Europe, large, flat church walls remained the perfect canvas for frescos. In Northern Europe, however, Gothic architecture replaced solid walls with massive windows, leading to the golden age of stained glass. By the 14th century, technological advances like "silver stain" allowed artists to paint complex details directly onto glass, which was then fired to create vibrant yellows and clears.

In the Low Countries, this obsession with detail culminated in the development of oil painting. Artists like Jan van Eyck used the slow-drying nature of oil to achieve "micro-realism"—capturing the texture of jewels, the reflection in a mirror, or the individual hairs of a fur coat. This Northern Gothic style was so advanced in its naturalism that it functioned as a parallel to the Italian Renaissance, achieving a different kind of "truth" through observation rather than classical geometry.

Image from Wikipedia

14th Century International Gothic Mary Magdalene in St. Johns' Cathedral in Toruń, Poland

The Lady and the Unicorn, the title given to a series of six tapestries woven in Flanders, this one being called À Mon Seul Désir; late 15th century; wool and silk; 377 x 473 cm; Musée de Cluny, Paris

Simone Martini (1285–1344)

Part of German stained glass panel of 1444 with the Visitation; pot metal of various colours, including white glass, black vitreous paint, yellow silver stain, and the "olive-green" parts are enamel. The plant patterns in the red sky are formed by scratching away black paint from the red glass before firing. A restored panel with new lead cames

Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux, by Jean Pucelle, Paris, 1320s

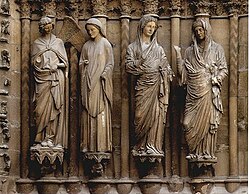

South portal of Chartres Cathedral (c. 1215–20).

West portal at Reims Cathedral, Annunciation group.

Nicola Pisano, Nativity and Adoration of the Magi from the pulpit in the Pisa Baptistery, 1260.

Claus Sluter, Daniel and Jesaiah from the Well of Moses, 1350–1406.

Base of the Holy Thorn Reliquary, French (Paris), 1390s, a Resurrection of the Dead in gold, enamel and gems.

Man of Sorrows (copy) on the main portal of Ulm Münster by Hans Multscher, 1429.

Panelled altarpiece section with Resurrection of Christ, English Nottingham alabaster, 1450–90, with remains of paint.

Later Gothic depiction of the Adoration of the Magi from Strasbourg Cathedral.

Detail of the Last Supper from Tilman Riemenschneider's Altar of the Holy Blood, 1501–05, carved limewood, Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Bavaria.