General relativity

Gravity is not a force pulling objects, but the physical geometry of space and time bending under weight.

Gravity is not a force pulling objects, but the physical geometry of space and time bending under weight.

In the Newtonian view, gravity was an invisible tug-of-war between masses. Einstein realized something more profound: space and time are joined into a single four-dimensional "fabric" called spacetime. When a massive object like the Sun sits in this fabric, it creates a dip or a curve. Planets don't orbit because they are being "pulled" by a tether; they are simply following the straightest possible path through a space that has been warped into a bowl.

This shift means gravity is a property of the universe’s shape, not an interactive energy. Einstein’s "happiest thought" was the Equivalence Principle: the realization that the feeling of being pulled down by gravity is identical to the feeling of being accelerated. If you were in a windowless elevator in deep space being pushed upward, you couldn't perform any experiment to prove you weren't just standing still on Earth.

Massive objects act as "time anchors," causing clocks to tick slower as gravity increases.

Massive objects act as "time anchors," causing clocks to tick slower as gravity increases.

One of the most counterintuitive consequences of general relativity is that time is not a universal constant. Because space and time are linked, the same mass that curves space also stretches time. This phenomenon, called gravitational time dilation, means that time passes more slowly near a massive body than it does further away.

This isn't just a theoretical curiosity; it has measurable stakes. Your head technically ages slightly faster than your feet because it is further from the Earth’s center. On a larger scale, the atomic clocks on GPS satellites must be programmed to compensate for the fact that they are further out in the Earth's "gravity well." Without these relativistic adjustments, GPS locations would drift by several kilometers every single day.

Light does not travel in straight lines, but follows the "dents" left by stars and galaxies.

Light does not travel in straight lines, but follows the "dents" left by stars and galaxies.

While we think of light as the ultimate straight edge, general relativity proves that it must follow the curvature of spacetime. When starlight passes near a massive object like a sun or a galaxy, the path of the light bends. This effect, known as gravitational lensing, allows astronomers to use massive clusters of galaxies as "natural telescopes" to see objects sitting directly behind them.

This was the "smoking gun" that proved Einstein right. During a solar eclipse in 1919, Arthur Eddington observed stars near the rim of the Sun and found they appeared slightly out of position. The Sun’s mass had physically shifted the path of the starlight. This discovery instantly turned Einstein into a global celebrity and ended the 200-year reign of Newtonian physics.

The theory predicts "holes" in the universe where the laws of physics essentially break.

The theory predicts "holes" in the universe where the laws of physics essentially break.

General relativity isn't just about subtle shifts in time; it predicts extreme environments where the curvature of spacetime becomes infinite. These are black holes—regions where mass is so concentrated that the "dip" in spacetime becomes a bottomless pit from which even light cannot escape. At the center lies a singularity, a point where our mathematical understanding of the universe stops making sense.

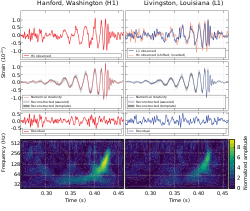

Beyond static holes, the theory also predicts that when massive objects accelerate—like two black holes colliding—they send ripples through the fabric of the universe itself. These "gravitational waves" were finally detected in 2015. They allow us to "hear" the universe's most violent events, providing a way to observe the cosmos without using light at all.

General relativity is perfectly accurate, yet it is fundamentally incompatible with the rest of science.

General relativity is perfectly accurate, yet it is fundamentally incompatible with the rest of science.

Despite a century of being proven right in every experiment, general relativity has a "glitch": it does not play well with quantum mechanics. Relativity is a "classical" theory—it deals with the smooth, predictable, and continuous fabric of the very large. Quantum mechanics deals with the jittery, probabilistic, and discrete world of the very small.

When scientists try to use Einstein’s equations to explain the subatomic center of a black hole, the math returns "infinity" and breaks down. This conflict is the greatest unsolved mystery in modern physics. We have two separate "operating systems" for reality—one for the stars and one for the atoms—and so far, no one has found the "Theory of Everything" that can merge them into a single file.

According to general relativity, objects in a gravitational field behave similarly to objects within an accelerating enclosure. For example, an observer will see a ball fall the same way in a rocket (left) as it does on Earth (right), provided that the acceleration of the rocket is equal to 9.8 m/s2 (the acceleration due to gravity on the surface of the Earth).

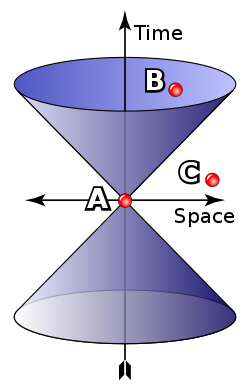

Light cone of event A

Schematic representation of the gravitational redshift of a light wave escaping from the surface of a massive body

Deflection of light (sent out from the location shown in blue) near a compact body (shown in gray)

Newtonian (red) vs. Einsteinian orbit (blue) of a lone planet orbiting a star. The influence of other planets is ignored.

Orbital decay for PSR J0737−3039: time shift, tracked over 16 years (2021).

Einstein cross: four images of the same astronomical object, produced by a gravitational lens

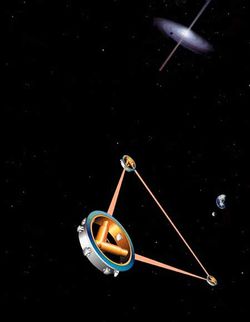

Artist's impression of the space-borne gravitational wave detector LISA

Simulation based on the equations of general relativity: a star collapsing to form a black hole while emitting gravitational waves

This blue horseshoe is a distant galaxy that has been magnified and warped into a nearly complete ring by the strong gravitational pull of the massive foreground luminous red galaxy.

Penrose–Carter diagram of an infinite Minkowski universe

The ergosphere of a rotating black hole, which plays a key role when it comes to extracting energy from such a black hole

Projection of a Calabi–Yau manifold, one of the ways of compactifying the extra dimensions posited by string theory

Simple spin network of the type used in loop quantum gravity

Observation of gravitational waves from binary black hole merger GW150914