Friedrich Nietzsche

Nietzsche’s early brilliance made him the youngest-ever professor of classics, but chronic illness forced him into a decade of nomadic solitude.

Nietzsche’s early brilliance made him the youngest-ever professor of classics, but chronic illness forced him into a decade of nomadic solitude.

At just 24, Nietzsche was appointed Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel—an achievement so rare he hadn't even finished his doctorate or teaching certificate at the time. His background was deeply rooted in language and the study of Greek tragedy, but he quickly became a "stateless" intellectual, renouncing his Prussian citizenship and eventually his academic career.

Plagued by migraines, digestive issues, and failing eyesight, he resigned from the university in 1879. This physical decline paradoxically fueled his most productive period. For the next ten years, he lived in various boarding houses across Italy and Switzerland, writing the core texts that would eventually dismantle Western metaphysics. He lived as an outsider, increasingly isolated from his former mentors like Richard Wagner and his academic peers.

He diagnosed the "Death of God" not as an atheist triumph, but as a terrifying cultural crisis that demanded a total revaluation of values.

He diagnosed the "Death of God" not as an atheist triumph, but as a terrifying cultural crisis that demanded a total revaluation of values.

Nietzsche’s most famous declaration—the "death of God"—was a warning that the traditional moral foundations of Europe were collapsing, leaving a void of nihilism in their wake. He argued that truth is not an objective reality but a "perspectivism," shaped by competing internal drives. To survive the loss of divine authority, he believed humanity needed to move beyond "slave morality"—the Christian valuing of humility and pity—and embrace a "master morality" of self-creation and strength.

To fill the void, he introduced the Übermensch (Overman), a figure who creates their own meaning and values through the "will to power." This wasn't a call for physical domination, but for the creative power of the individual to overcome cultural mores. He paired this with the "eternal return," a thought experiment asking if you could live your life exactly as it is, over and over, forever—an ultimate test of life-affirmation.

A decade of feverish creativity ended in a spectacular mental collapse that left Nietzsche silent for his final eleven years.

A decade of feverish creativity ended in a spectacular mental collapse that left Nietzsche silent for his final eleven years.

In 1889, at age 44, Nietzsche suffered a complete mental breakdown in Turin, Italy. Legend suggests he collapsed while weeping and embracing a horse that was being whipped in the street. He never recovered his faculties, spending his remaining years in a state of paralysis and vascular dementia, cared for by his mother and sister.

During this period of silence, his fame began to explode across Europe. Ironically, the man who spent his life writing about the "creative powers of the individual" was entirely unaware that he was becoming the most talked-about philosopher in the world. He died in 1900, leaving behind a massive cache of unpublished notebooks and a reputation that was about to be hijacked.

His sister’s ideological forgery branded Nietzsche a Nazi, a distortion that took mid-century scholars decades to undo.

His sister’s ideological forgery branded Nietzsche a Nazi, a distortion that took mid-century scholars decades to undo.

After his collapse, Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, took control of his manuscripts. An ardent ultranationalist and antisemite, she edited and organized his unpublished notes to align with her own ideology. Her version of The Will to Power was curated to support German nationalism, directly contradicting Nietzsche’s own written disdain for antisemitism and "German-ness."

Because of her manipulations, Nietzsche’s work became a staple of Nazi propaganda. It wasn't until the 1950s and 60s that scholars like Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale cleared the air, publishing corrected editions that restored his original intent. This "restored" Nietzsche became the bedrock for existentialism, postmodernism, and almost every major movement in 20th-century continental philosophy.

Image from Wikipedia

Young Nietzsche, 1861

Young Nietzsche, 1864

Arthur Schopenhauer strongly influenced Nietzsche's philosophical thought.

Left to right: Erwin Rohde, Karl von Gersdorff and Nietzsche, October 1871

Nietzsche, c. 1872

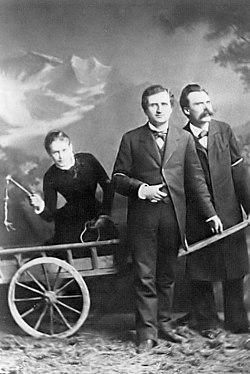

Lou Salomé, Paul Rée and Nietzsche posing for a studio photo during their trip through Italy in 1882, planning to establish an educational commune together, but the friendship disintegrated in late 1882 due to complications from Rée's and Nietzsche's mutual romantic interest in Salomé.

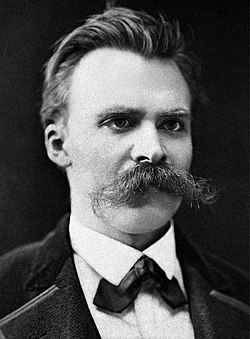

Photo of Nietzsche by Gustav-Adolf Schultze, 1882

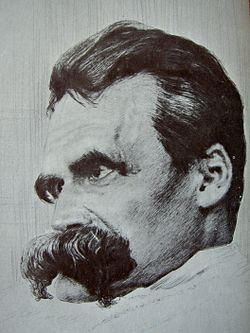

Drawing by Hans Olde from the photographic series The Ill Nietzsche, late 1899

Nietzsche in the care of his sister, 1899

After the breakdown, Peter Gast "corrected" Nietzsche's writings without his approval.

Nietzsche's grave at Röcken in Germany

Bust of Nietzsche, by Max Klinger, 1903–1904, at the Städel, Frankfurt

The residence of Nietzsche's last three years along with archive in Weimar, Germany, which holds many of Nietzsche's papers

Portrait of Nietzsche by Edvard Munch, 1906, at the Thiel Gallery, Stockholm