French cuisine

French cuisine began as a theater of sensory excess before evolving into a disciplined, codified science.

French cuisine began as a theater of sensory excess before evolving into a disciplined, codified science.

In the Middle Ages, aristocratic dining was defined by service en confusion, where all dishes were presented simultaneously in a chaotic display of wealth. Visual spectacle often outweighed flavor; chefs used juices from spinach and leeks to dye food vibrant colors, and elaborate "showpiece" dishes involved sewing cooked meat back into the skins of swans or peacocks, gilding their beaks with gold leaf.

This theatrical approach gradually shifted toward structure. Early pioneers like Guillaume Tirel (Taillevent) and later François Pierre La Varenne began moving away from heavy, spice-laden medieval sauces toward indigenous French flavors and lighter preparations. By the 17th century, the foundation of haute cuisine was laid, moving the focus from the quantity of food on the table to the technical precision of the recipe.

The fall of the guild system during the French Revolution transformed cooking from a restricted craft into a national industry.

The fall of the guild system during the French Revolution transformed cooking from a restricted craft into a national industry.

For centuries, the French culinary world was governed by a rigid guild system that acted as a barrier to entry. Guilds were siloed: "Butchers" could only sell raw meat, while "Rôtisseurs" could only sell roasted meats. This restricted competition and kept culinary knowledge within closed circles. If you weren't part of a guild, you couldn't legally sell prepared food to the public.

The French Revolution abolished these guilds, effectively "democratizing" the kitchen. For the first time, any cook had the legal right to produce and sell any culinary item they wished. This deregulation, combined with the displacement of royal chefs who no longer had aristocrats to cook for, led to the birth of the modern restaurant industry, as talented chefs began opening their own establishments for the public.

Marie-Antoine Carême turned cooking into architecture by codifying the "Mother Sauces" that still anchor Western kitchens.

Marie-Antoine Carême turned cooking into architecture by codifying the "Mother Sauces" that still anchor Western kitchens.

Often called the "Chef of Kings and King of Chefs," Carême was obsessed with order and grandiosity. Before his influence, sauces were inconsistent and varied wildly between kitchens. Carême simplified this complexity into a system of "foundations" or fonds, known as Mother Sauces: espagnole, velouté, and béchamel. By mastering these bases, a chef could create hundreds of derivative sauces.

Carême’s genius was in his ability to codify. He wrote massive, authoritative texts that standardized French cooking for the first time. He viewed the kitchen through the lens of an architect, famous for his pièces montées—extravagant, inedible pastry structures used as centerpieces. His work ensured that French technique could be taught systematically in culinary schools across the globe.

Auguste Escoffier modernized fine dining by applying military-style efficiency to the professional kitchen.

Auguste Escoffier modernized fine dining by applying military-style efficiency to the professional kitchen.

In the late 19th century, Georges Auguste Escoffier overhauled how professional kitchens functioned by introducing the brigade system. Instead of one cook struggling to prepare an entire dish from start to finish, the kitchen was divided into specialized stations (e.g., the saucier for sauces, the rôtisseur for roasts, the entremettier for vegetables).

This division of labor drastically reduced preparation time and allowed for service à la russe—serving meals in separate courses on individual plates—which is the standard for modern fine dining. Escoffier’s masterpiece, Le Guide Culinaire, further refined French cuisine by de-emphasizing heavy, flour-thickened sauces in favor of lighter fumets (essences), creating the blueprint for the 20th-century restaurant.

French gastronomy is protected as a global cultural heritage, underpinned by strict regional laws and universal education standards.

French gastronomy is protected as a global cultural heritage, underpinned by strict regional laws and universal education standards.

French cuisine is not merely a collection of recipes; it is a regulated system of identity. The Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) laws ensure that products like Champagne or Roquefort cheese can only be produced in specific regions using traditional methods. This ensures that "terroir"—the unique flavor of a specific geography—remains central to the cuisine's value.

The global dominance of French cooking is maintained through its role as the "gold standard" for culinary education. Most Western culinary boards use French criteria as their baseline. This cultural weight was officially recognized in 2010 when UNESCO added French gastronomy to its "Intangible Cultural Heritage" list, marking the first time a nation’s food culture was granted such status.

A nouvelle cuisine presentation

French haute cuisine presentation

French wines are usually made to accompany French cuisine.

John, Duke of Berry enjoying a grand meal. The Duke is sitting with a cardinal at the high table, under a luxurious baldaquin, in front of the fireplace, tended to by several servants, including a carver. On the table to the left of the Duke is a golden salt cellar, or nef, in the shape of a ship; illustration from Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, circa 1410.

The Polish wife of Louis XV, Queen Marie Leszczyńska, influenced French cuisine.

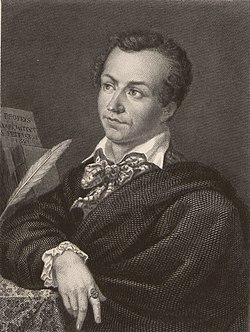

Marie-Antoine Carême was a French chef and an early practitioner and exponent of the elaborate style of cooking known as grande cuisine

Georges Auguste Escoffier was a French chef, restaurateur, and culinary writer who popularized and updated traditional French cooking methods

Basil salmon terrine

Bisque is a smooth and creamy French potage.

Foie gras with mustard seeds and green onions in duck jus

Blanquette de veau

Typical French pâtisserie

Mille-feuille

Macaron

Éclair