Free will

Free will is defined by three distinct levers: the capacity to choose, the engine of moral responsibility, and the "ultimate authorship" of an action.

Free will is defined by three distinct levers: the capacity to choose, the engine of moral responsibility, and the "ultimate authorship" of an action.

While often used colloquially, "free will" in philosophy refers to specific metrics of agency. It is the ability to select between real possibilities, the control necessary to justify praise or blame (moral desert), and the requirement that an individual be the "first cause" (causa sui) of their behavior. Without these, concepts like advice, persuasion, and prohibition lose their logical footing.

The debate is rarely about whether we feel free—most humans possess a powerful sense of agency—but whether that feeling is an accurate reflection of reality or a sophisticated illusion. This tension creates a "dilemma of determinism": if our actions are just the next step in a billion-year chain of cause and effect, the foundations of law and ethics may require a total conceptual overhaul.

The "Consequence Argument" suggests that if the past and the laws of physics are fixed, our future choices are merely inevitable outputs.

The "Consequence Argument" suggests that if the past and the laws of physics are fixed, our future choices are merely inevitable outputs.

Incompatibilists argue that free will and a deterministic universe cannot coexist. Their logic is grounded in the "causal chain": if the laws of nature and the events of the remote past are not up to us, then the consequences of those things (including our current thoughts) are also not up to us. To be truly free, an agent must be the "ultimate source," a starting point that isn't merely a reaction to prior stimuli.

Hard determinists accept this logic and conclude that free will is an impossibility, comparing humans to "wind-up toys" or "billiard balls" governed by physics. Metaphysical libertarians, conversely, argue that because we clearly have free will, determinism must be false. A third, more radical group—hard incompatibilists—argues that neither a determined universe nor a random (indeterministic) one allows for free will, as randomness is just as outside our control as a fixed script.

Compatibilism redefines freedom not as the absence of physical cause, but as the presence of reason and the lack of coercion.

Compatibilism redefines freedom not as the absence of physical cause, but as the presence of reason and the lack of coercion.

The majority of modern philosophers identify as compatibilists, viewing the standoff between free will and determinism as a false dilemma. They argue that "freedom" doesn't require us to break the laws of physics; it simply requires that our actions flow from our internal desires and rational deliberations rather than external force. If you sit on a sofa because you want to, you are free—even if that "want" was technically the result of prior neural states.

Some "hard compatibilists" go further, arguing that determinism is actually necessary for free will. Without a predictable, cause-and-effect universe, our choices would be erratic and untethered from our characters. To these thinkers, freedom isn't the ability to have done otherwise in the exact same circumstances, but the capacity to respond to reasons and adjust behavior based on potential consequences.

The concept shifted from the Ancient Greek focus on "control" to a Christian focus on the "lack of necessity" in the human soul.

The concept shifted from the Ancient Greek focus on "control" to a Christian focus on the "lack of necessity" in the human soul.

The problem of free will is one of the longest-running debates in Western thought. Ancient Greeks like Aristotle and Epictetus focused on "up-to-us-ness"—the idea that nothing hindered an individual from choosing a specific path. By the 3rd century CE, Alexander of Aphrodisias began framing the issue through causal undeterminism, arguing that control requires the ability to decide between opposites regardless of prior conditions.

The specific term "free will" (liberum arbitrium) was popularized by 4th-century Christian theology. During this era, and until the Enlightenment, it generally meant a "lack of necessity" in the human will—the idea that the soul is not compelled by nature to act. This theological shift moved the focus from external physical constraints to the internal mechanics of the human spirit.

Science challenges agency by viewing the brain as a chain of physical dominoes where even quantum randomness fails to provide "control."

Science challenges agency by viewing the brain as a chain of physical dominoes where even quantum randomness fails to provide "control."

Physical determinism treats the brain as a macroscopic object governed by the same laws as a row of falling dominoes. If neural activity is just a series of electrochemical reactions necessitated by prior states, "choice" becomes a retrospective label for a mechanical process. While quantum mechanics introduces indeterminism (randomness) at a microscopic level, most philosophers argue this doesn't help the case for free will; being ruled by a "random dice roll" is no more liberating than being ruled by a "fixed gear."

The debate persists because the "intuitive evidence" of conscious decision-making is difficult to reconcile with a "causal closure" of the physical world—the idea that every physical event must have a physical cause. This remains the core friction point between neuroscience and philosophy: if the mind is what the brain does, and the brain follows physical laws, then the "self" may be a passenger rather than the driver.

A biker performing a dirt jump, according to some interpretations, is the result of free will.

A domino's movement is determined completely by laws of physics.

A simplified taxonomy of philosophical positions regarding free will and determinism

Various definitions of free will that have been proposed for Metaphysical Libertarianism (agent/substance causal, centered accounts, and efforts of will theory), along with examples of other common free will positions (Compatibilism, Hard Determinism, and Hard Incompatibilism). Red circles represent mental states; blue circles represent physical states; arrows describe causal interaction.

A simplified taxonomy of philosophical positions regarding free will and theological determinism

René Descartes

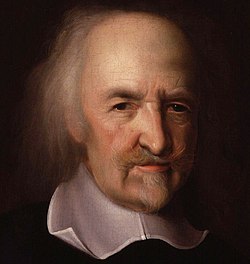

Thomas Hobbes was a classical compatibilist.

Baruch Spinoza thought that there is no free will.

Arthur Schopenhauer claimed that phenomena do not have freedom of the will, but the will as noumenon is not subordinate to the laws of necessity (causality) and is thus free.

Augustine's view of free will and predestination would go on to have a profound impact on Christian theology.

Bas relief of Maimonides in the U.S. House of Representatives