Natural selection

Natural selection is a statistical filter that transforms random variation into non-random adaptation.

Natural selection is a statistical filter that transforms random variation into non-random adaptation.

The process relies on three simple ingredients: variation, inheritance, and differential reproductive success. Within any population, individuals possess different traits; some of these traits are heritable; and some of those heritable traits provide a better chance of surviving and breeding. Over generations, the "useful" traits accumulate while the detrimental ones vanish.

It is less a "force" and more a mathematical inevitability. If you have entities that replicate with slight errors in a resource-limited environment, those better suited to the environment will necessarily become more common. This simple logic explains the entire complexity of the biosphere without the need for an external designer.

"Survival of the fittest" is a misleading shorthand for "reproduction of the adequate."

"Survival of the fittest" is a misleading shorthand for "reproduction of the adequate."

The popular phrase suggests a violent struggle for individual survival, but in biological terms, "fitness" is strictly a measure of how many offspring an organism leaves behind. A long-lived, powerful animal that never reproduces has a biological fitness of zero, whereas a short-lived, sickly organism that produces a dozen surviving offspring is highly fit.

Natural selection doesn't require "perfection," only that an organism is slightly better at surviving to reproductive age than its neighbor. It is a "tinkerer" rather than an engineer, often recycling existing structures for new purposes—which is why the human eye is remarkably complex but still possesses a blind spot where the wiring is installed backward.

The "Modern Synthesis" solved Darwin’s biggest problem by merging his theory with genetics.

The "Modern Synthesis" solved Darwin’s biggest problem by merging his theory with genetics.

Darwin understood that traits were passed down, but he had no idea how. He feared that "blending inheritance"—the idea that offspring are a simple average of their parents—would eventually dilute all unique variations into a grey mediocrity. This was the "black box" of 19th-century biology.

The discovery of Mendelian genetics in the early 20th century provided the missing link. We now know that traits are passed as discrete units (genes) that don't blend away. The Modern Synthesis unified Darwinian selection with genetic math, proving that even a tiny survival advantage in a single gene can eventually sweep through an entire population.

Selection acts on the physical body, but its lasting effects are written in the gene pool.

Selection acts on the physical body, but its lasting effects are written in the gene pool.

Biologists distinguish between the "phenotype" (the physical traits and behaviors of an organism) and the "genotype" (the underlying genetic code). Natural selection can only "see" the phenotype—it doesn't care about the DNA, only whether the animal is fast enough to catch prey.

However, because the phenotype is built by the genotype, the deaths of individuals change the frequency of genes in the next generation. This creates a feedback loop: the environment filters the bodies, which in turn reshapes the "instruction manual" for the species. Over time, this leads to "speciation," where populations become so genetically distinct they can no longer interbreed.

Evolution has no foresight and lacks an ultimate "goal" or upward trajectory.

Evolution has no foresight and lacks an ultimate "goal" or upward trajectory.

A common misconception is that natural selection is an "escalator" leading toward greater complexity or "higher" forms of life like humans. In reality, selection is purely reactive. If an environment becomes stable and simple, selection may favor the loss of complex organs to save energy—this is why cave-dwelling fish often lose their eyes.

Selection cannot plan for future catastrophes; it only optimizes for the "now." A trait that is highly beneficial today (like a thick coat of fur in a cold climate) can become a lethal liability tomorrow if the climate shifts. Because it lacks a goal, evolution is characterized by "path dependency"—it can only work with what is already there, leading to the bizarre "jury-rigged" anatomy found throughout the animal kingdom.

A diagram demonstrating mutation and selection

Aristotle considered whether different forms could have appeared, only the useful ones surviving.

Modern biology began in the nineteenth century with Charles Darwin's work on evolution by natural selection.

Part of Thomas Malthus's table of population growth in England 1780–1810, from his Essay on the Principle of Population, 6th edition, 1826

Charles Darwin noted that pigeon fanciers had created many kinds of pigeon, such as Tumblers (1, 12), Fantails (13), and Pouters (14) by selective breeding.

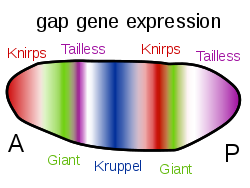

Evolutionary developmental biology relates the evolution of form to the precise pattern of gene activity, here gap genes in the fruit fly, during embryonic development.

During the Industrial Revolution, pollution killed many lichens, leaving tree trunks dark. A dark (melanic) morph of the peppered moth largely replaced the formerly usual light morph (both shown here). Since the moths are subject to predation by birds hunting by sight, the colour change offers better camouflage against the changed background, suggesting natural selection at work.

1: directional selection: a single extreme phenotype favoured.2, stabilizing selection: intermediate favoured over extremes.3: disruptive selection: extremes favoured over intermediate.X-axis: phenotypic traitY-axis: number of organismsGroup A: original populationGroup B: after selection

Different types of selection act at each life cycle stage of a sexually reproducing organism.

The peacock's elaborate plumage is mentioned by Darwin as an example of sexual selection, and is a classic example of Fisherian runaway, driven to its conspicuous size and coloration through mate choice by females over many generations.

Selection in action: resistance to antibiotics grows through the survival of individuals less affected by the antibiotic. Their offspring inherit the resistance.