Dust Bowl

Federal policy and a marketing myth turned the "Great American Desert" into a fragile agricultural powder keg.

Federal policy and a marketing myth turned the "Great American Desert" into a fragile agricultural powder keg.

Early explorers originally deemed the High Plains—the land west of the 100th meridian—unsuitable for European-style agriculture due to its lack of timber and surface water. However, the federal government aggressively incentivized settlement through the Homestead Acts, offering 160-to-640-acre plots to anyone willing to farm them. This expansion was fueled by "rain follows the plow," a pseudo-scientific belief popularized by real estate promoters who argued that the very act of tilling the soil would permanently increase the region's rainfall.

The timing was a trap: a series of unusually wet years in the early 20th century seemed to confirm this myth. Encouraged by high wheat prices during World War I and the disruption of Russian grain supplies, farmers tripled their cultivated acreage. They ignored the region's natural cycle of extreme drought, replacing the drought-resistant shortgrass prairie biome with thirsty commodity crops. When the rain inevitably stopped in 1930, the "Great American Desert" returned with a vengeance.

The rapid mechanization of the 1920s stripped the plains of the deep-rooted grasses that had anchored the soil for millennia.

The rapid mechanization of the 1920s stripped the plains of the deep-rooted grasses that had anchored the soil for millennia.

The catastrophe was as much a technological failure as a climatic one. The introduction of small gasoline tractors and combine harvesters allowed farmers to perform "deep plowing" on a massive scale. This process displaced the native, deep-rooted grasses that had historically trapped moisture and held the soil in place even during high winds. Without these biological anchors, the virgin topsoil was reduced to a fine, friable powder.

By the time the drought hit its peak in the mid-1930s, 100 million acres of land had been turned into a loose dust bed. In the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles, cotton farmers worsened the situation by leaving fields bare during the winter—the season of the highest winds—and burning stubble to control weeds. This deprived the soil of the last vestiges of organic nutrients and surface cover, leaving nothing to stop the wind from lifting the earth into the sky.

The resulting "Black Blizzards" were more than just storms—they were static-charged walls of earth that blotted out the sun across the continent.

The resulting "Black Blizzards" were more than just storms—they were static-charged walls of earth that blotted out the sun across the continent.

The dust storms, or "black rollers," were unlike any meteorological event previously recorded. They were massive, opaque clouds of black and gray silt that could reduce visibility to less than three feet. The friction of the dust particles generated enough static electricity to short out car engines and knock people unconscious with a simple handshake. On "Black Sunday" in April 1935, a single storm traveled at 60 mph, plunging the plains into such total darkness that there wasn't enough oxygen to keep a kerosene lamp lit.

These storms were not localized events; they were continental disasters. Great Plains topsoil was carried thousands of miles east, depositing 12 million pounds of dust on Chicago and blotting out the Statue of Liberty and the U.S. Capitol. In the winter of 1934, the phenomenon even produced "red snow" across New England. The term "Dust Bowl" itself was coined by an Associated Press editor while rewriting a story about the Boise City, Oklahoma, "Black Sunday" event.

The exodus of 3.5 million people created a social upheaval where the "Okie" identity masked a complex shift in American social mobility.

The exodus of 3.5 million people created a social upheaval where the "Okie" identity masked a complex shift in American social mobility.

The environmental collapse forced one of the largest migrations in American history. Between 1930 and 1940, roughly 3.5 million people abandoned the Plains states. While these migrants were collectively and often pejoratively labeled "Okies," they came from across the heartland, including Arkansas, Missouri, and Texas. Many headed to California, arriving to find that the Great Depression had made the "Golden State" nearly as economically desolate as the homes they had left behind.

Surprisingly, data shows that only 43% of these migrants were farm laborers immediately before moving; nearly a third were professional or white-collar workers. This mass movement actually facilitated a degree of social mobility: while many farmers were forced into unskilled labor in California, they eventually transitioned into semi-skilled or high-skilled fields that paid better than their original farms. By the end of the 1930s, those who had migrated were generally better off than the "stay-at-homes" who struggled to survive on ruined land.

Arthur Rothstein's Farmer and Sons Walking in the Face of a Dust Storm, a Resettlement Administration photograph taken in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, in April 1936

Map of states and counties affected by the Dust Bowl between 1935 and 1938, originally prepared by the Soil Conservation Service. The most severely affected counties during this period are colored .

A dust storm approaches Stratford, Texas, in 1935.

A dust storm; Spearman, Texas, April 14, 1935

Heavy black clouds of dust rising over the Texas Panhandle, Texas, c. 1936

U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST on April 15, 1935, just after one of the most severe dust storms

Buried machinery in a barn lot; Dallas, South Dakota, May 1936

"Broke, baby sick, and car trouble!" – Dorothea Lange's 1937 photo of a Missouri migrant family's jalopy stuck near Tracy, California.

A migratory family from Texas living in a trailer in an Arizona cotton field

Resettlement Administration poster by Richard H. Jansen, 1935

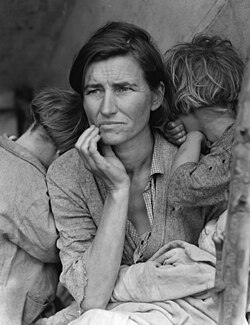

Florence Owens Thompson seen in the photo Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange

"Dust bowl farmers of west Texas in town", photograph taken by Dorothea Lange, June 1937, in Anton, Texas.