DNA

DNA is a structural masterpiece of antiparallel strands anchored by a rigid sugar-phosphate backbone.

DNA is a structural masterpiece of antiparallel strands anchored by a rigid sugar-phosphate backbone.

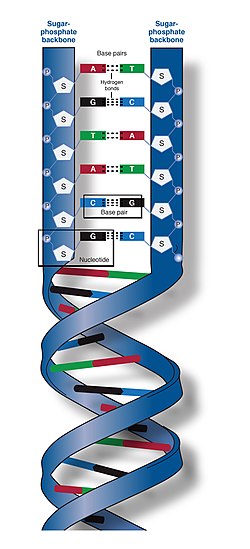

The molecule is a "polynucleotide," a long-chain polymer made of repeating units called nucleotides. Each unit consists of a phosphate group, a deoxyribose sugar, and one of four nitrogenous bases. These units are linked by covalent phosphodiester bonds, forming an alternating sugar-phosphate "backbone." Crucially, the two strands run in opposite directions—one 5' to 3' and the other 3' to 5'—a configuration known as "antiparallel" that is essential for how the molecule is read and replicated.

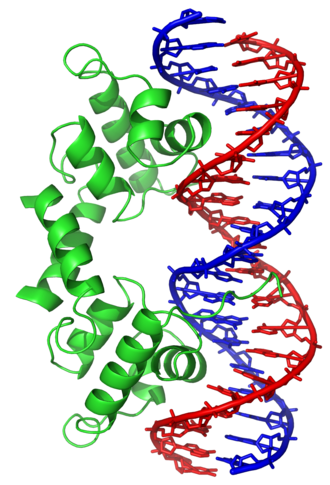

The resulting double helix isn't a smooth cylinder; it features two distinct "grooves" known as the major and minor grooves. Because the strands are not symmetrical, the major groove is wider (2.2 nm) than the minor groove (1.2 nm). This physical gap is vital for life: the major groove provides enough space for transcription factors and other proteins to "read" the chemical signatures of the bases inside without unzipping the entire molecule.

Genetic instructions are encoded in the sequence of four nitrogenous bases acting as a universal biological alphabet.

Genetic instructions are encoded in the sequence of four nitrogenous bases acting as a universal biological alphabet.

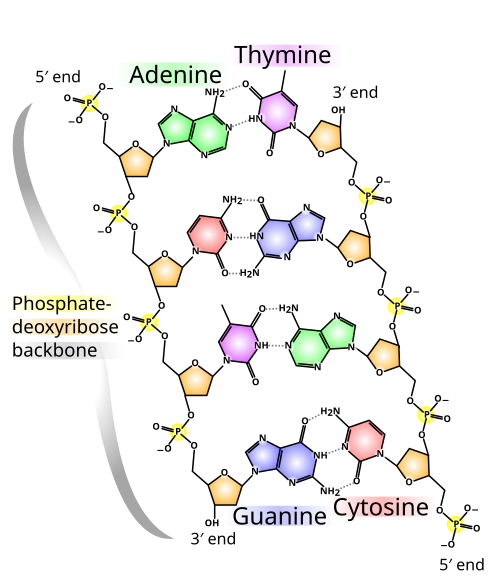

The actual "data" of life is stored in the sequence of four bases: Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Guanine (G), and Cytosine (C). These are divided into two shapes: double-ringed purines (A and G) and single-ringed pyrimidines (C and T). According to strict base-pairing rules, A always bonds with T, and C always bonds with G. This complementarity is the magic of DNA—it means each strand contains a perfect "negative" of the other, allowing information to be copied with near-perfect fidelity during cell division.

To turn this code into a living organism, the cell uses a two-step translation process. First, DNA is transcribed into RNA, a similar but more transient molecule. In this process, Thymine is replaced by Uracil (U). These RNA "messages" are then translated into specific sequences of amino acids to build proteins. While the backbone is the physical frame, it is the linear order of these four letters that dictates every biological trait, from the color of a flower to the complexity of the human brain.

Organisms manage extreme physical length through dense architectural packing and specialized compartmentalization.

Organisms manage extreme physical length through dense architectural packing and specialized compartmentalization.

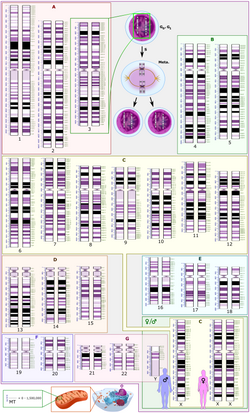

The scale of DNA is staggering. In a single human cell, the diploid genome contains over 6 billion base pairs. If you were to straighten out the DNA from just one cell, it would be approximately two meters long. To fit this into a microscopic nucleus, DNA is wrapped around proteins called histones to form chromatin, which then folds into the dense structures we know as chromosomes.

Not all DNA lives in the same place. In eukaryotes (like humans, plants, and fungi), the majority of DNA is protected inside the cell nucleus, but small "satellite" genomes exist in the mitochondria and chloroplasts. Prokaryotes (like bacteria), however, lack a nucleus entirely and store their DNA in a circular chromosome within the cytoplasm. This difference in storage highlights two distinct evolutionary paths: one focused on massive, protected complexity and the other on streamlined efficiency.

Molecular stability is a precision trade-off between chemical "zippering" and the requirements of replication.

Molecular stability is a precision trade-off between chemical "zippering" and the requirements of replication.

The two strands of the double helix are held together by hydrogen bonds, which are significantly weaker than the covalent bonds forming the backbone. This is a functional feature, not a flaw: it allows the DNA to "zip" and "unzip" like a coat fastener. The strength of this bond depends on the specific sequence; C-G pairs have three hydrogen bonds, while A-T pairs only have two. Consequently, DNA with high "GC-content" is more stable and harder to "melt" into single strands.

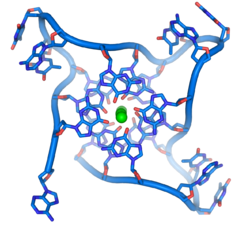

Beyond simple zippering, DNA is dynamic. It can undergo "supercoiling," where the molecule twists like a phone cord to become more compact or to regulate access to its code. Furthermore, DNA is not static after it is built; it can be modified by the addition of methyl groups to "non-canonical" bases. These modifications act as a molecular volume knob, turning genes up or down without changing the underlying code—a field of study known as epigenetics that explains how the same genome can produce hundreds of different cell types.

A chromosome and its packaged long strand of DNA unraveled. The DNA's base pairs encode genes, which provide functions. A human DNA can have up to 500 million base pairs with thousands of genes.

The structure of the DNA double helix (type B-DNA). The atoms in the structure are colour-coded by element and the detailed structures of two base pairs are shown in the bottom right.

Simplified diagram

Chemical structure of DNA; hydrogen bonds shown as dotted lines. Each end of the double helix has an exposed 5' phosphate on one strand and an exposed 3′ hydroxyl group (—OH) on the other.

DNA major and minor grooves. The latter is a binding site for the Hoechst stain dye 33258.

Top, a GC base pair with three hydrogen bonds. Bottom, an AT base pair with two hydrogen bonds. Non-covalent hydrogen bonds between the pairs are shown as dashed lines.

Schematic karyogram of a human. It shows 22 homologous chromosomes, both the female (XX) and male (XY) versions of the sex chromosome (bottom right), as well as the mitochondrial genome (to scale at bottom left). The blue scale to the left of each chromosome pair (and the mitochondrial genome) shows its length in terms of millions of DNA base pairs.Further information: Karyotype

From left to right, the structures of A, B and Z-DNA

DNA quadruplex formed by telomere repeats. The looped conformation of the DNA backbone is very different from the typical DNA helix. The green spheres in the center represent potassium ions.

Impure DNA extracted from an orange

![A covalent adduct between a metabolically activated form of benzo[a]pyrene, the major mutagen in tobacco smoke, and DNA](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d8/Benzopyrene_DNA_adduct_1JDG.png/250px-Benzopyrene_DNA_adduct_1JDG.png)

A covalent adduct between a metabolically activated form of benzo[a]pyrene, the major mutagen in tobacco smoke, and DNA

Location of eukaryote nuclear DNA within the chromosomes

DNA replication: The double helix is unwound by a helicase and topoisomerase. Next, one DNA polymerase produces the leading strand copy. Another DNA polymerase binds to the lagging strand. This enzyme makes discontinuous segments (called Okazaki fragments) before DNA ligase joins them together.

Interaction of DNA (in orange) with histones (in blue). These proteins' basic amino acids bind to the acidic phosphate groups on DNA.

The lambda repressor helix-turn-helix transcription factor bound to its DNA target