Deontology

Morality is found in the nature of the act itself, rather than the wreckage or wealth it leaves behind.

Morality is found in the nature of the act itself, rather than the wreckage or wealth it leaves behind.

Deontology, derived from the Greek déon (duty), posits that the rightness of an action is determined by its adherence to rules rather than its results. It stands in direct opposition to consequentialism—the "ends justify the means" approach. In a deontological framework, certain actions are inherently right or wrong; for instance, lying is considered wrong even if it prevents a minor inconvenience or produces a happy outcome.

This "duty-based" approach focuses on the "Good Will." According to this logic, an action only has moral worth if it is performed out of a sense of obligation. If you help someone because you enjoy the praise or fear a penalty, the action might be helpful, but it isn't "right" in the strictest moral sense. The motive is the moral engine, not the destination.

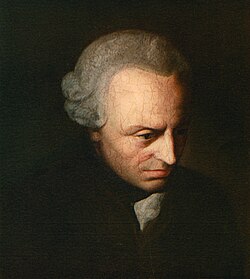

Immanuel Kant argued that a moral rule is only valid if you would be willing to make it a universal law for everyone.

Immanuel Kant argued that a moral rule is only valid if you would be willing to make it a universal law for everyone.

Kantianism is the most influential form of deontology. Kant proposed the "Categorical Imperative," a mental test for any action: if everyone in the world did this, would society still function? If you lie to get out of trouble, you must imagine a world where everyone lies to get out of trouble. In such a world, the concept of "truth" would vanish, making the lie itself ineffective. Therefore, lying is irrational and immoral.

Kant also famously insisted that humanity must always be treated as an "end" and never merely as a "means to an end." This forbids using people as tools, even for a "greater good." This rigor is why Kantian deontology is often seen as uncompromising; he famously argued that it is wrong to lie even to a murderer looking for a victim, because an exception for one person destroys the universality of the principle of truth.

Deontology isn't always a single rule; it can be a "plurality" of conflicting duties that must be balanced.

Deontology isn't always a single rule; it can be a "plurality" of conflicting duties that must be balanced.

Not all deontologists follow Kant’s singular focus. W.D. Ross argued for "pluralistic deontology," suggesting we have seven prima facie (at first sight) duties, such as fidelity (keeping promises), gratitude, and non-injury. Unlike Kant’s absolute rules, Ross acknowledged that these duties can clash.

When duties conflict—like when keeping a promise to a friend would cause physical harm to a stranger—Ross argued we must use our "moral maturity" to decide which duty is absolute in that specific situation. This version of the theory is more flexible than Kant’s, allowing for a "threshold" where the weight of one duty (like saving a life) clearly overrides another (like telling the truth).

Modern "threshold deontology" attempts to bridge the gap between rigid rules and the reality of catastrophic consequences.

Modern "threshold deontology" attempts to bridge the gap between rigid rules and the reality of catastrophic consequences.

One of the harshest criticisms of deontology is that it can lead to "moral fanaticism"—following a rule even if it leads to the destruction of the world. To counter this, threshold deontologists argue that rules should govern our behavior up to a point, but if the consequences of following a rule become sufficiently "dire," a consequentialist approach takes over.

Contemporary philosophers like Frances Kamm have refined these rules further through the "Principle of Permissible Harm." This addresses the famous "Trolley Problem": why is it okay to flip a switch to save five people by killing one, but not okay to kill one healthy person to harvest their organs for five patients? Kamm suggests that harm is only permissible if it is an aspect or effect of the greater good itself, rather than the direct tool used to achieve it.

Immanuel Kant