Maize

A wild Mexican grass was radically engineered into the world’s most productive grain.

A wild Mexican grass was radically engineered into the world’s most productive grain.

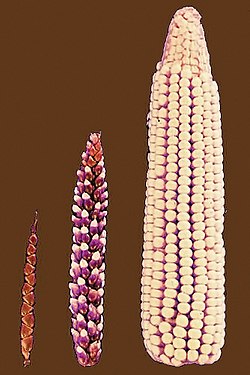

Unlike wheat or rice, which resemble their wild ancestors, maize looks nothing like teosinte, the spindly grass from which it descended. Roughly 9,000 years ago, indigenous farmers in the Balsas River Valley of Mexico began a process of artificial selection so intensive that the modern plant can no longer reproduce without human intervention. Its seeds are trapped behind a tough husk, preventing natural dispersal.

This evolutionary leap created a "giant" among cereals. A single seed of maize can yield a plant that produces hundreds of kernels, a ratio of return that far outpaces other staple crops. This massive caloric surplus provided the foundational energy for the rise of the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations.

The plant operates as a hyper-efficient solar engine built for rapid growth.

The plant operates as a hyper-efficient solar engine built for rapid growth.

Maize utilizes C4 photosynthesis, a more advanced chemical pathway than the C3 method used by most plants. This allows maize to concentrate carbon dioxide more effectively, enabling it to grow faster and use water more efficiently, especially in high-temperature and high-light environments. It is essentially a biological machine designed to turn sunlight into starch at maximum speed.

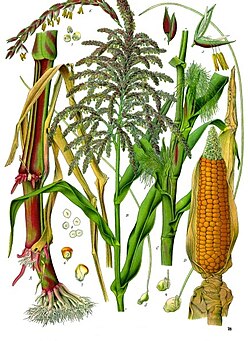

Physically, the plant is unique for being monoecious—it has separate male (the tassel) and female (the ear) flowers on the same plant. This separation makes it incredibly easy for humans to control breeding. By physically removing tassels, farmers can force cross-pollination between specific varieties, leading to the "hybrid vigor" that caused yields to skyrocket in the 20th century.

Ancient chemical processing unlocked the grain’s hidden nutrition.

Ancient chemical processing unlocked the grain’s hidden nutrition.

While maize is high in energy, its nutrients are naturally locked away. Mesoamerican cultures discovered "nixtamalization"—soaking the grain in an alkaline solution like lime water. This process breaks down the hemicellulose in the cell walls and releases niacin (Vitamin B3) and essential amino acids, making the grain a complete nutritional source.

When maize was first exported to Europe and Africa, explorers brought the seed but left the nixtamalization technique behind. The result was widespread outbreaks of pellagra, a horrific deficiency disease. It took centuries for the rest of the world to realize that the "primitive" lime-soaking method was actually a sophisticated bit of biochemical engineering necessary for survival on a corn-heavy diet.

Maize serves as the invisible foundation of the modern industrial economy.

Maize serves as the invisible foundation of the modern industrial economy.

Although we see sweet corn in grocery stores, the vast majority of global production is "dent corn," a commodity crop rarely eaten directly by humans. Instead, maize is the primary feedstock for the global meat industry, converted into beef, pork, and poultry. It is the silent ingredient in the modern supermarket, appearing as high-fructose corn syrup, corn starch, and citric acid in thousands of processed products.

Beyond food, maize is a major industrial fuel. In the United States, roughly 40% of the corn crop is distilled into ethanol to be blended into gasoline. This dual role as both food and fuel makes maize prices a critical driver of global economic stability; when the price of corn spikes, the cost of everything from a gallon of gas to a dozen eggs follows.

The crop’s volatile genome changed our understanding of how DNA works.

The crop’s volatile genome changed our understanding of how DNA works.

Maize has an unusually "plastic" and complex genome, which made it the perfect subject for groundbreaking genetic research. In the 1940s, Barbara McClintock discovered "jumping genes" (transposons) while studying the mosaic colors of maize kernels. These are DNA sequences that move from one location to another, proving that genomes are not static blueprints but dynamic, changing environments.

Today, maize is the most heavily modified crop on Earth. The majority of the global harvest consists of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) engineered for herbicide resistance or to produce their own pesticides (Bt corn). This high-tech genetic profile allows for massive monocultures, though it remains a point of intense debate regarding biodiversity and the long-term resilience of the global food supply.

Botanical illustration showing male and female flowers

Image from Wikipedia

Many small male flowers make up the tassel.

Female inflorescence, with young silk

Stalks, ears and silk

Full-grown maize plants

Mature maize ear on a stalk

Male flowers

Mature silk

Exotic varieties are collected to add genetic diversity when selectively breeding new domestic strains.

Teosinte (left), maize-teosinte hybrid (middle), maize (right)

Ancient Mesoamerican relief sculpture of maize, National Museum of Anthropology of Mexico

Cultivation of maize, illustrated in the 16th-century Florentine Codex

Seedlings three weeks after sowing

Young stalks