Cognitive dissonance

We are biologically wired to treat mental friction as a physical discomfort that must be resolved.

We are biologically wired to treat mental friction as a physical discomfort that must be resolved.

Cognitive dissonance is not just a "difference of opinion" within one's mind; it is a state of psychological tension that functions much like hunger or thirst. When our actions clash with our beliefs—like a health-conscious person who smokes— the brain experiences a genuine "drive state" to reduce the resulting distress. We cannot function long-term in a state of internal contradiction, so the mind compulsively seeks to restore "consonance" or harmony.

This resolution rarely involves admitting we were wrong. Instead, we typically take the path of least resistance: we change our attitudes to match our actions, justify the behavior by adding new "rational" thoughts, or simply ignore any information that highlights the conflict. The goal of the brain isn't necessarily to find the truth, but to maintain a stable, consistent self-image.

The "Boring Task" experiment proved that small rewards create stronger internal belief changes than large ones.

The "Boring Task" experiment proved that small rewards create stronger internal belief changes than large ones.

In 1959, Leon Festinger conducted a counter-intuitive study that remains a pillar of social psychology. Participants performed an incredibly dull task, then were paid either $1 or $20 to tell the next person the task was "exciting." Logic suggests those paid $20 would believe the lie more, but the opposite happened. Those paid $20 had a clear external justification for lying (the money), so they felt no internal conflict and still thought the task was boring.

However, the participants paid only $1 experienced intense dissonance. A single dollar wasn't enough to justify a lie, so to resolve the discomfort, they actually convinced themselves that the task really was fun. This "induced compliance" effect shows that when we are persuaded to do something for a minimal reward, we are far more likely to change our private opinions to align with that action.

We value goals and groups more intensely when the "cost of entry" involves pain or effort.

We value goals and groups more intensely when the "cost of entry" involves pain or effort.

Effort justification explains why rituals like fraternity hazing, grueling military basic training, or expensive luxury brand loyalty are so effective. If a person undergoes a difficult or humiliating experience to achieve something, and that thing turns out to be mediocre, they face massive dissonance: "I am a smart person, yet I suffered for nothing."

To escape this mental trap, the brain inflates the value of the goal. The person concludes that the group is more elite, the goal more sacred, or the product more superior than it actually is. We don't just endure suffering to get what we want; we learn to love what we suffered for because the alternative—admitting the effort was wasted—is too painful to accept.

When a core prophecy fails, true believers often double down rather than admit they were wrong.

When a core prophecy fails, true believers often double down rather than admit they were wrong.

One of the most famous applications of this theory involved Festinger infiltrating a cult that believed the world would end on a specific date. When the world did not end, the members did not abandon the cult in embarrassment. Instead, they claimed their devotion had "saved the world," becoming even more fervent in their proselytizing.

By recruiting more members, the group sought "social validation" to drown out the dissonance of the failed prophecy. If more people believe it, it must be true. This demonstrates that when a belief is central to a person's identity, providing contradictory evidence can backfire, causing the individual to entrench themselves further in the falsehood to protect their ego.

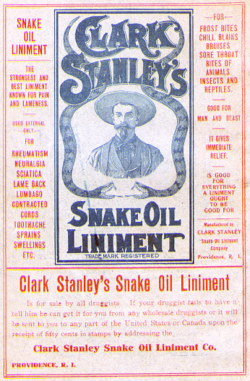

After performing dissonant behavior (lying) a person might find external, consonant elements. Therefore, a snake oil salesman might find a psychological self-justification (great profit) for promoting medical falsehoods, but, otherwise, might need to change his beliefs about the falsehoods.

In the fable of "The Fox and the Grapes", by Aesop, on failing to reach the desired bunch of grapes, the fox then decides he does not truly want the fruit because it is sour. The fox's act of rationalization (justification) reduced his anxiety over the cognitive dissonance from the desire he cannot realise.

Dissonant self-perception: A lawyer can experience cognitive dissonance if he must defend as innocent a client he thinks is guilty. From the perspective of The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance: A Current Perspective (1969), the lawyer might experience cognitive dissonance if his false statement about his guilty client contradicts his identity as a lawyer and an honest man.

The biomechanics of cognitive dissonance: MRI evidence indicates that the greater the psychological conflict signalled by the anterior cingulate cortex, the greater the magnitude of the cognitive dissonance experienced by the person.