Citizen Kane

Orson Welles leveraged a "blank check" contract to secure unprecedented creative freedom.

Orson Welles leveraged a "blank check" contract to secure unprecedented creative freedom.

Following the notoriety of his 1938 War of the Worlds radio broadcast, the 24-year-old Welles was courted by RKO Pictures with a contract that scandalized the industry. While most directors were subject to studio oversight, Welles was granted "final cut" privilege, the right to select his own cast and crew, and total artistic control—provided he stayed within a $500,000 budget.

This autonomy allowed Welles to treat the RKO lot like "the greatest electric train set a boy ever had." Because he was a newcomer to film, he was unburdened by "the right way" to make movies, leading him to experiment with deep focus cinematography and non-linear storytelling that seasoned directors of the era likely would have deemed too risky or technically impossible.

The screenplay inverted the American "success story" into a fragmented study of personal failure.

The screenplay inverted the American "success story" into a fragmented study of personal failure.

Welles and co-writer Herman J. Mankiewicz set out to create a "failure story" rather than a traditional narrative of action. The plot follows a reporter’s search for the meaning of "Rosebud," the final word of media tycoon Charles Foster Kane. Instead of a chronological biography, the film is a mosaic of conflicting perspectives from Kane’s associates, suggesting that a single life cannot be fully understood through a newsreel obituary.

The character of Kane was a thinly veiled composite of American barons, most notably William Randolph Hearst. The "Rosebud" mystery—revealed to the audience as a childhood sled—symbolizes the innocence and maternal security Kane lost when he was traded away to a bank for a fortune. It suggests that despite his immense wealth and power, Kane remained a boy striking out at the world that took him from his home.

A powerful media mogul attempted to erase the film from history before its release.

A powerful media mogul attempted to erase the film from history before its release.

William Randolph Hearst was so offended by the film’s parallels to his private life that he prohibited any mention of Citizen Kane in his chain of newspapers. This media blackout, combined with the film’s unconventional structure, led to a disappointing box office performance. Although critically acclaimed upon arrival, the film failed to recoup its costs and quickly faded from public consciousness.

The suppression was nearly successful until the mid-1950s. The film’s "resurrection" began in France, where critics like André Bazin praised its technical depth. A 1956 re-release and subsequent television broadcasts allowed a new generation of filmmakers and scholars to rediscover its innovations, eventually cementing its reputation as the foundational text of modern cinema.

Technical innovations in cinematography and sound redefined the visual language of movies.

Technical innovations in cinematography and sound redefined the visual language of movies.

Citizen Kane is celebrated as a "precedent-setting" film largely due to the collaboration between Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland. They popularized "deep focus," a technique where the foreground, middle ground, and background are all in sharp focus simultaneously. This forced the audience to look around the frame for meaning, rather than being told where to look by the camera.

The film also integrated Welles’s background in radio. He used "lightning mixes" to link different scenes through continuous sound and employed a complex narrative structure that jumped through decades. From Robert Wise’s sharp editing to Bernard Herrmann’s evocative score, every department utilized the studio's resources to push the boundaries of what 1940s technology could achieve.

Poster showing two women in the bottom left of the picture looking up toward a man in a white suit in the top right of the picture. "Everybody's talking about it. It's terrific!" appears in the top left of the picture. "Orson Welles" appears in block letters between the women and the man in the white suit. "Citizen Kane" appears in red and yellow block letters tipped 60° to the right. The remaining credits are listed in fine print in the bottom right.

Favored to win election as governor, Kane makes a campaign speech at Madison Square Garden.

Harry Shannon, George Coulouris and Agnes Moorehead

Welles's 1938 radio broadcast of "The War of the Worlds" caught the attention of RKO studio chief George J. Schaefer.

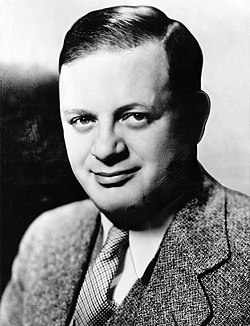

Orson Welles at his Hollywood home in 1939, during the long months it took to launch his first film project

Herman J. Mankiewicz co-wrote the script in early 1940. He and Welles separately re-wrote and revised each other's work until Welles was satisfied with the finished product.

The Mercury Theatre was an independent repertory theatre company founded by Orson Welles and John Houseman in 1937. The company produced theatrical presentations, radio programs, films, promptbooks and phonographic recordings.

Sound stage entrance, as seen in the Citizen Kane trailer

Cinematographer Gregg Toland wanted to work with Welles for the opportunity of trying experimental camera techniques that other films did not allow.

Aerial view of Otto Hermann Kahn's Oheka Castle that portrays the fictional Xanadu

Welles fell ten feet (3.0 m) while shooting the scene in which Kane shouts at the departing Boss Jim W. Gettys; his injuries required him to direct from a wheelchair for two weeks.

Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland prepare to film the post-election confrontation between Kane and Leland, shot from an extremely low angle that required cutting into the set floor.

Kane ages convincingly in the breakfast montage, make-up artist Maurice Seiderman's tour de force

Incidental music includes the publisher's theme, "Oh, Mr. Kane", a tune by Pepe Guízar with special lyrics by Herman Ruby.

Orson Welles and Ruth Warrick in the breakfast montage