Circadian rhythm

Life follows a self-sustaining internal metronome that persists even in total darkness

Life follows a self-sustaining internal metronome that persists even in total darkness

While we often think of "feeling tired" as a reaction to the sun setting, the circadian rhythm is actually an endogenous, self-sustained oscillation. It doesn't just react to the environment; it anticipates it. In 1729, French scientist Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan noticed that mimosa plants continued to open and close their leaves on schedule even when kept in a dark closet, proving that the timer is built into the organism itself.

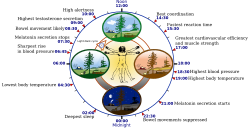

This internal clock regulates everything from body temperature and heart rate to hormone secretion and cognitive performance. It operates on a cycle slightly longer than 24 hours in most humans, requiring constant "resetting" by external cues to stay aligned with the rotating Earth.

The brain’s master clock uses light to "handshake" with the planet’s rotation

The brain’s master clock uses light to "handshake" with the planet’s rotation

The conductor of this biological orchestra is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a tiny region of the brain located in the hypothalamus. The SCN receives direct input from specialized photosensitive cells in the retina. These cells aren't for seeing shapes; they are light-level sensors that tell the brain whether it is day or night, allowing the SCN to synchronize thousands of peripheral clocks throughout the body.

When the SCN detects darkness, it triggers the pineal gland to release melatonin, the signal for "biological night." Conversely, morning light suppresses melatonin and spikes cortisol to wake the system up. This is why looking at blue-light-emitting screens at night is so disruptive; it sends a "false morning" signal to the SCN, halting the transition to sleep.

Proteins rise and fall in a mechanical feedback loop that builds time from scratch

Proteins rise and fall in a mechanical feedback loop that builds time from scratch

At the cellular level, the clock is powered by a "transcription-translation feedback loop." Three scientists won the 2017 Nobel Prize for discovering that specific genes (like Period and Cryptochrome) produce proteins that accumulate in the cell overnight. Once these proteins reach a certain concentration, they shut off their own production.

As the proteins degrade over the day, the inhibition is lifted, and the cycle starts again. This elegant chemical seesaw takes almost exactly 24 hours to complete. Because this mechanism exists in nearly every cell in your body, your liver, heart, and skin are all effectively "keeping time" independently, though they look to the brain's SCN for the master signal.

The 24-hour cycle is an ancient evolutionary shield against DNA damage

The 24-hour cycle is an ancient evolutionary shield against DNA damage

Circadian rhythms are not unique to humans; they are found in almost all living things, including fungi, plants, and even ancient cyanobacteria. Evolution likely favored these rhythms because they allowed organisms to perform sensitive metabolic tasks—like DNA replication—at night, protecting their genetic material from the high UV radiation of midday sun.

In plants, the rhythm controls fragrance release to attract pollinators at the right time and manages water retention. In animals, it creates "temporal niches," allowing some species to dominate the day (diurnal) and others the night (nocturnal), effectively doubling the utility of a single habitat.

Modern "circadian misalignment" acts as a silent catalyst for chronic disease

Modern "circadian misalignment" acts as a silent catalyst for chronic disease

The friction between our ancestral biological clocks and our 24/7 modern lifestyle is a major driver of metabolic and psychological illness. Shift work, "social jetlag," and constant indoor lighting create a state of chronic misalignment where the brain thinks it’s noon but the digestive system thinks it’s midnight.

This desynchronization is linked to increased risks of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease because the body cannot efficiently process nutrients or repair cells when "out of phase." Researchers are now focusing on chronotherapy—timing the delivery of medications (like chemotherapy or blood pressure drugs) to match the body's natural peaks and valleys for maximum efficacy and minimum side effects.

Image from Wikipedia

Sleeping tree by day and night

Graph showing timeseries data from bioluminescence imaging of circadian reporter genes. Transgenic seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana were imaged by a cooled CCD camera under three cycles of 12h light: 12h dark followed by 3 days of constant light (from 96h). Their genomes carry firefly luciferase reporter genes driven by the promoter sequences of clock genes. The signals of seedlings 61 (red) and 62 (blue) reflect transcription of the gene CCA1, peaking after lights-on (48h, 72h, etc.). Seedlings 64 (pale grey) and 65 (teal) reflect TOC1, peaking before lights-off (36h, 60h, etc.). The timeseries show 24-hour, circadian rhythms of gene expression in the living plants.

Key centers of the mammalian and Drosophila brains (A) and the circadian system in Drosophila (B)

Molecular interactions of clock genes and proteins during Drosophila circadian rhythm

A variation of an eskinogram illustrating the influence of light and darkness on circadian rhythms and related physiology and behavior through the suprachiasmatic nucleus in humans

When eyes receive light from the sun, the pineal gland's production of melatonin is inhibited, and the hormones produced keep the human awake. When the eyes do not receive light, melatonin is produced in the pineal gland and the human becomes tired.

CircadianLux light at the JCCPA that support circadian rhythm indoors

A short nap during the day does not affect circadian rhythms.