Chocolate

Chocolate began as a bitter, sacred beverage with a linguistic identity that remains a mystery.

Chocolate began as a bitter, sacred beverage with a linguistic identity that remains a mystery.

While popularly associated with the Aztecs and Mayans, the cacao tree was first used for food in present-day Ecuador roughly 5,300 years ago. For millennia, chocolate was strictly a liquid, often fermented into alcohol by the Olmecs or served as a frothy, bitter drink flavored with chili and vanilla. To these civilizations, cacao was a divine gift, used as medicine, ritual offering, and even currency.

The word "chocolate" itself is a linguistic puzzle. While many believe it derives from the Nahuatl xocoatl ("bitter drink"), scholars find this phonetically unlikely. A more probable origin is the Nawat word chikola:tl, possibly referring to the wooden whisk used to foam the drink. It wasn't until the late 16th century that "chocolate" became the generic term for cacao-based beverages in the Spanish-speaking world.

The Industrial Revolution transformed chocolate from an exclusive liquid luxury into a mass-market solid.

The Industrial Revolution transformed chocolate from an exclusive liquid luxury into a mass-market solid.

For nearly three centuries after arriving in Europe, chocolate remained a drink for the societal elite, often associated with the Catholic aristocracy. The transition to the solid bars we recognize today was driven by 19th-century engineering. In 1828, Coenraad van Houten patented a press to remove cocoa butter from the "liquor," creating "Dutch cocoa" and paving the way for large-scale production.

Subsequent inventions like the melanger (mixing machine) and the conche (refiner) allowed for a smoother texture and the integration of milk solids. By 1890, a single worker could produce fifty times more chocolate than their pre-industrial counterpart. This shift moved production away from the Americas toward massive plantations in Asia and Africa, opening up a global mass market for snacks and confectionery.

Achieving chocolate’s signature "snap" and silkiness requires precise chemical manipulation of fat crystals.

Achieving chocolate’s signature "snap" and silkiness requires precise chemical manipulation of fat crystals.

Raw chocolate is naturally gritty and temperamental. To make it "tongue-detectable" smooth, it undergoes conching, a process where metal beads grind cocoa and sugar particles down to roughly 20 micrometers. Following this, the chocolate must be tempered. Because cocoa butter is a polymorphic fat, it can crystallize into six different forms, but only "Form V" provides the glossy finish and crisp snap consumers expect.

If stored improperly, chocolate undergoes "blooming"—a process where fat or sugar crystals migrate to the surface, creating a dusty white film. While visually unappealing, bloom is harmless and does not affect the taste. It is essentially a physical sign that the chocolate has lost its tempered structure due to fluctuations in temperature or humidity.

The hierarchy of dark, milk, and white chocolate is defined by the shifting ratios of cocoa solids and fats.

The hierarchy of dark, milk, and white chocolate is defined by the shifting ratios of cocoa solids and fats.

All traditional chocolate is built from the same base: the cacao nib, which is ground into "chocolate liquor" (a mix of solids and butter). Dark chocolate is the purest form, defined primarily by its cocoa percentage and the absence of milk. Milk chocolate replaces a significant portion of those cocoa solids with milk solids, resulting in a milder, creamier profile that dominates the global snack market.

White chocolate is often the subject of culinary debate because it contains no non-fat cocoa solids at all. It is made exclusively from cocoa butter, sugar, and milk. Because it lacks the fibrous solids of the bean, it retains an ivory color and a different melt-profile, but it remains legally classified as chocolate because of its cocoa butter foundation.

Modern chocolate production relies on a West African supply chain shadowed by systemic human rights crises.

Modern chocolate production relies on a West African supply chain shadowed by systemic human rights crises.

Today, approximately 60% of the world’s cocoa is produced in just two countries: Ivory Coast and Ghana. This concentration of production has led to significant ethical scrutiny. Reports of child labor, trafficking, and "de facto slavery" have plagued the industry since the early 20th century, with major British producers facing boycotts as early as 1908.

Despite a century of industry promises and the rise of "bean-to-bar" trade models, these issues persist in the 21st century. The pressure for low-cost, mass-produced chocolate continues to conflict with the labor costs required for ethical harvesting, making the chocolate bar a complex intersection of affordable luxury and global inequality.

Chocolate bars in dark, white, and milk varieties (top to bottom)

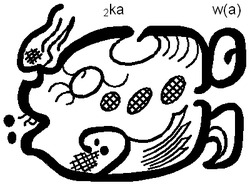

The Maya glyph for cacao

Mexica. Man Carrying a Cacao Pod, 1440–1521

One of the first mass-produced chocolate bars, Fry's Chocolate Cream, was produced by Fry's in 1866.

Barks made of different varieties of chocolate

Chocolate is created from the cocoa bean. A cacao tree with fruit pods in various stages of ripening.

Fermenting cocoa beans

A chocolate mill (right) grinds and heats cocoa kernels into chocolate liquor. A melanger (left) mixes milk, sugar, and other ingredients into the liquor.

A longitudinal conche

A chocolate bar in a bowl of melted chocolate

Packaged chocolate in the Ghirardelli Chocolate Company

Chocolate with various fillings

Child drying cacao in Chuao, Venezuela

A Cadbury chocolate bar

Chocolate cake with chocolate frosting