Chernobyl disaster

The worst nuclear accident in history was triggered by a safety test meant to prevent one.

The worst nuclear accident in history was triggered by a safety test meant to prevent one.

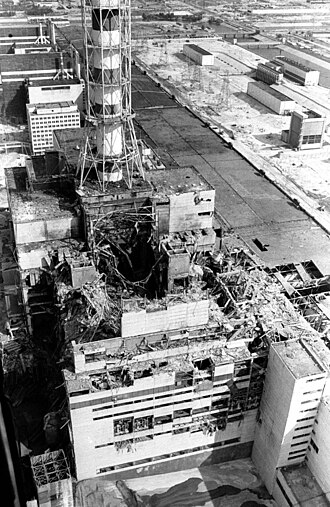

On April 26, 1986, reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded during a simulation of a station blackout. The irony of the disaster lies in its purpose: engineers were trying to prove that the rotational momentum of a spinning turbine could provide enough residual electricity to power cooling pumps during the 60-second gap before backup diesel generators kicked in.

The test had failed three times in previous years. In their determination to succeed, operators disabled the Emergency Core Cooling System (ECCS) and other vital safety protocols. This turned a routine maintenance window into a high-stakes experiment on a live reactor, ultimately costing an estimated $700 billion—the most expensive disaster in human history.

A ten-hour delay forced an unprepared night shift to manage a "poisoned" reactor.

A ten-hour delay forced an unprepared night shift to manage a "poisoned" reactor.

The test was originally scheduled for the day shift, who had been specifically briefed on the procedure. However, a regional power grid controller in Kiev delayed the shutdown for nearly ten hours to meet evening electricity demands. By the time the test finally began at 11:04 PM, the day and evening shifts had departed, leaving the complex operation to a night shift that had little time to prepare.

During the delay, the reactor power dropped too low, leading to "xenon poisoning"—a buildup of xenon-135, which absorbs neutrons and inhibits the nuclear chain reaction. To compensate and regain power, operators pulled almost all of the reactor’s control rods out of the core. This left the plant in an extremely unstable state, similar to a car with its engine redlining while the brakes are completely removed.

The RBMK reactor design contained a lethal physics "trap" called a positive void coefficient.

The RBMK reactor design contained a lethal physics "trap" called a positive void coefficient.

Unlike most Western reactors, the Soviet RBMK design had a "positive void coefficient." In this setup, if the cooling water turns to steam (forming "voids"), the nuclear reaction actually speeds up because steam absorbs fewer neutrons than liquid water. This creates a dangerous positive feedback loop: more heat creates more steam, which creates more heat.

When the test began and the water flow slowed down, steam bubbles rapidly formed in the core. Because the reactor was already unstable and the safety systems were disabled, there was nothing to check the sudden power excursion. Within seconds, a massive power surge caused steam explosions that ruptured the reactor building and ignited a graphite fire that burned for days, lofting radioactive contaminants across the Soviet Union and Europe.

The human toll remains a subject of intense scientific and political debate.

The human toll remains a subject of intense scientific and political debate.

The immediate impact was clear: two engineers died in the blast, and 134 workers were hospitalized with Acute Radiation Syndrome (ARS), 28 of whom died within months. To contain the site, the Soviet Union mobilized over 500,000 "liquidators" and evacuated 117,000 people from a 30-kilometer Exclusion Zone that remains largely uninhabited today.

Long-term health statistics are more controversial. While the UN Scientific Committee estimates fewer than 100 deaths directly from fallout, other studies, including a 2006 WHO report, project up to 9,000 cancer deaths across Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. The most concrete medical legacy is a "large fraction" of 6,000 childhood thyroid cancer cases attributed to the consumption of contaminated milk in the weeks following the explosion.

Containment is a century-long engineering project that won't end until 2065.

Containment is a century-long engineering project that won't end until 2065.

Immediately after the disaster, crews constructed a concrete "sarcophagus" to seal the ruins, but it was a temporary fix prone to leaking. In 2016, the New Safe Confinement—the largest moveable metal structure ever built—was slid into place over the old reactor. This massive arch is designed to prevent further leaks and allow for the robotic dismantling of the melted core.

The cleanup is far from over. Current schedules suggest that the removal of reactor debris and the full decontamination of the site will not be completed until at least 2065. The city of Pripyat remains a ghost town, replaced by the purpose-built city of Slavutych, which was constructed to house the plant's displaced workers and their families.

Image from Wikipedia

Reactor decay heat shown as % of thermal power from time of sustained fission shutdown using two different correlations. Due to decay heat, solid fuel power reactors need high flows of coolant after a fission shutdown for a considerable time to prevent fuel cladding damage, or in the worst case, a full core meltdown.

Process flow diagram of the reactor

Size comparison of Generation II reactor vessels, a design classification of commercial reactors built until the end of the 1990s. The RBMK reactor is depicted as a mauve rectangle.

Plan view of reactor No. 4 core. The number on each control rod indicates the insertion depth in centimeters one minute prior to the disaster. neutron detectors (12) control rods (167) short control rods from below reactor (32) automatic control rods (12) pressure tubes with fuel rods (1661)

Steam plumes continued to be generated days after the initial explosion.

Firefighter Leonid Telyatnikov being decorated for bravery

Video still image showing a graphite moderator block ejected from the core

Pripyat with the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in the distance

Ruins of abandoned house in Chernobyl, 2019

Abandoned objects in the evacuation zone

Picture taken by French satellite SPOT-1 on 1 May 1986

Chernobyl lava-like corium, formed by fuel-containing mass, flowed into the basement of the plant.

Extremely high levels of radioactivity in the lava under the Chernobyl number four reactor in 1986

STR-1 robot used in cleanup, nicknamed "Moon Walker"