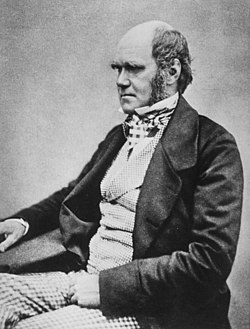

Charles Darwin

Darwin’s path to revolutionary science was forged through academic failure and a "gentleman’s" obsession with collecting.

Darwin’s path to revolutionary science was forged through academic failure and a "gentleman’s" obsession with collecting.

Before he was a titan of biology, Darwin was a medical school dropout who found surgical theaters distressing and lectures dull. His father, fearing he would become an idle "shooting man," sent him to Cambridge to become a country parson. This pivot was ironic: while training for the clergy, Darwin became "the man who walks with Henslow," a botany professor who mentored his passion for natural history and secured his spot on the HMS Beagle.

His early education was less about formal curriculum and more about radical subcultures. In Edinburgh, he learned taxidermy from John Edmonstone, a freed enslaved man, and joined student societies where radical materialists challenged religious orthodoxy. These formative years replaced dogmatic theology with a rigorous habit of observation and a "burning zeal" for scientific travel.

Five years on the HMS Beagle transformed Darwin from a novice collector into a world-class geologist.

Five years on the HMS Beagle transformed Darwin from a novice collector into a world-class geologist.

Though famous for biology, Darwin spent most of his voyage on land investigating the earth's crust. Influenced by Charles Lyell’s theory that the earth changed through slow, gradual processes, Darwin applied this "uniformitarian" logic to everything he saw. He found fossilized seashells high in the Andes and giant extinct mammal bones in Patagonia that mirrored living species. These observations suggested that the earth—and the life upon it—was far older and more dynamic than then believed.

The Galápagos Islands were not an "eureka" moment but a slow-burning puzzle. Darwin initially failed to realize the significance of the tortoises and mockingbirds he encountered. It was only upon returning to England and organizing his notes that he realized the slight variations between island species "undermined the stability of Species." The voyage provided the raw data; the insight required years of quiet, domestic "investigation" back in England.

The core of Darwinism is the "branching" pattern of life driven by the non-miraculous process of natural selection.

The core of Darwinism is the "branching" pattern of life driven by the non-miraculous process of natural selection.

Darwin’s breakthrough was not proposing evolution—others had done that—but identifying its primary mechanism. He realized that in the "struggle for existence," favorable variations are preserved while others perish, a process he called natural selection. This mirrored the "artificial selection" used by farmers in breeding, but occurred over vast timescales without a conscious designer.

This theory replaced the "ladder of progress" with a "branching tree." It proposed that all life descended from a common ancestor, a concept that unified all biological sciences. Fearful of the social and religious fallout, Darwin sat on his theory for 20 years, only rushing to publish On the Origin of Species in 1859 after Alfred Russel Wallace independently hit upon the same idea.

Darwin’s influence extended far beyond biology, laying the groundwork for modern psychology and soil science.

Darwin’s influence extended far beyond biology, laying the groundwork for modern psychology and soil science.

While the public focused on "man coming from monkeys," Darwin was busy applying his theories to the minutiae of life. He published pioneering work on the coevolution of orchids and insects, and his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals was one of the first to use photography to argue that human emotions were evolved traits shared with other species. This effectively founded the field of comparative psychology.

Even his final work, a study on earthworms and "vegetable mould," was revolutionary. By proving that tiny creatures could reshape the planet's surface over time, he reinforced his lifelong theme: that small, incremental changes lead to massive, world-altering results. By the time of his death, he had shifted the human perspective from being a "separate creation" to being an integral, evolved part of the natural world.

Three-quarter length studio photo showing Darwin's characteristic large forehead and bushy eyebrows with deep-set eyes, pug nose, and mouth set in a determined look. He is bald on top, with dark hair and long side whiskers, but no beard or moustache. His jacket is dark, with very wide lapels, and his trousers are a light check pattern. His shirt features an upright wing collar, and his cravat is tucked into his waistcoat, which has a light, fine checked pattern.

A chalk drawing of the seven-year-old Darwin in 1816, with a potted plant, by Ellen Sharples. Part of a double portrait showing him together with his sister Catherine.

A bicentennial portrait by Anthony Smith of Darwin as a student, in the courtyard at Christ's College, Cambridge, where he had rooms.

The round-the-world voyage of the Beagle, 1831–1836

Darwin (right) on the Beagle's deck at Bahía Blanca in Argentina, with fossils; caricature by Augustus Earle, the initial ship's artist

As HMS Beagle surveyed the coasts of South America, Darwin theorised about geology and the extinction of giant mammals. Watercolour by the ship's artist Conrad Martens, who replaced Augustus Earle, in Tierra del Fuego.

While still a young man, Darwin joined the scientific elite; portrait by George Richmond.

In mid-July 1837 Darwin started his "B" notebook on Transmutation of Species, and on page 36 wrote "I think" above his first evolutionary tree.

Darwin's wife Emma Wedgwood

Darwin in 1842 with his eldest son, William Erasmus Darwin

Darwin's "sandwalk" at Down House in Kent was his usual "thinking path".

Darwin aged 46 in 1855, by then working towards publication of his theory of natural selection. He wrote to Joseph Hooker about this portrait, "if I really have as bad an expression, as my photograph gives me, how I can have one single friend is surprising."

In 1862 Darwin began growing his beard, as seen in the 1868 portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron.

An 1871 caricature following publication of The Descent of Man was typical of many showing Darwin with an ape body, identifying him in popular culture as the leading author of evolutionary theory.

By 1878, an increasingly famous Darwin had suffered years of illness.