Chaos theory

Chaos is not a lack of order, but a system that is fundamentally deterministic yet impossible to predict long-term.

Chaos is not a lack of order, but a system that is fundamentally deterministic yet impossible to predict long-term.

In common usage, "chaos" implies a total mess. In mathematics, it describes systems that follow strict, rigid rules but produce results that look like noise. Unlike a coin flip, which is truly random, a chaotic system—like a double pendulum or a weather pattern—operates on a specific set of equations. If you could measure the starting conditions with infinite precision, you could predict the outcome forever.

The problem is that "infinite precision" is physically impossible. In a chaotic system, the tiniest rounding error in your data doesn't just cause a small mistake in your prediction; it causes the prediction to fail completely over time. Chaos is the study of how simple, rule-based systems create complexity that defies our ability to foresee the future.

The "Butterfly Effect" proves that small differences don't stay small; they explode exponentially.

The "Butterfly Effect" proves that small differences don't stay small; they explode exponentially.

The hallmark of chaos is "sensitivity to initial conditions." In a stable system, a 1% error in measurement leads to a roughly 1% error in the result. In a chaotic system, that 1% error can double and redouble until it consumes the entire calculation. This is why a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil could, in theory, trigger a tornado in Texas weeks later.

This isn't a poetic metaphor for "everything is connected"; it is a literal description of how errors propagate. Mathematician Edward Lorenz discovered this while running weather simulations. When he entered "0.506" instead of "0.506127" into his computer, the simulated weather patterns diverged so wildly that they became unrecognizable. Small inputs are not "noise" to be ignored—they are the seeds of the eventual outcome.

Within the turbulence lies "Strange Attractors," the hidden blueprints that prevent total randomness.

Within the turbulence lies "Strange Attractors," the hidden blueprints that prevent total randomness.

If you plot the behavior of a chaotic system on a graph, it doesn't just fill the space with random dots. Instead, the system tends to orbit around specific shapes or states known as "Attractors." Even when the movement is unpredictable, it remains confined within a boundary. These shapes are often "Strange Attractors," which exhibit fractal geometry—meaning they look the same whether you zoom in or zoom out.

This reveals a profound truth: Chaos has an architecture. A waterfall is chaotic, but it always stays within the bounds of the "waterfall shape." The stock market is chaotic, but it follows certain cycles of volatility. We may not be able to predict the exact position of a point in the system at a specific time, but we can understand the "envelope" or the "climate" in which that system exists.

Chaos theory shattered the "Clockwork Universe" and forced science to embrace limits.

Chaos theory shattered the "Clockwork Universe" and forced science to embrace limits.

For centuries after Isaac Newton, scientists believed the universe was a giant clock. If you knew the position and velocity of every atom, you could calculate the entire past and future. Chaos theory, beginning with Henri Poincaré’s work on the "Three-Body Problem," killed this dream. It proved that even simple systems involving just three interacting objects (like the Sun, Earth, and Moon) can become mathematically "unsolvable" for the long term.

This realization shifted the goal of science from absolute prediction to "probabilistic modeling." We stopped trying to say exactly when it would rain and started looking for the boundaries of possibility. It moved us away from a world of linear cause-and-effect and toward a world of feedback loops, where the output of one moment becomes the input for the next.

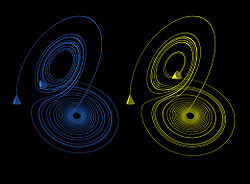

A plot of the Lorenz attractor for values r = 28, σ = 10, b = 8/3

A plot of the 3D Lorenz attractor

The map defined by x → 4 x (1 – x) and y → (x + y) mod 1 displays sensitivity to initial x positions. Here, two series of x and y values diverge markedly over time from a tiny initial difference.

The map defined by x → 4 x (1 – x) and y → (x + y) mod 1 also displays topological mixing. Here, the blue region is transformed by the dynamics first to the purple region, then to the pink and red regions, and eventually to a cloud of vertical lines scattered across the space.

The Lorenz attractor displays chaotic behavior. These two plots demonstrate sensitive dependence on initial conditions within the region of phase space occupied by the attractor.

Coexisting chaotic and non-chaotic attractors within the generalized Lorenz model. There are 128 orbits in different colors, beginning with different initial conditions for dimensionless time between 0.625 and 5 and a heating parameter r = 680. Chaotic orbits recurrently return close to the saddle point at the origin. Nonchaotic orbits eventually approach one of two stable critical points, as shown with large blue dots. Chaotic and nonchaotic orbits occupy different regions of attraction within the phase space.

Bifurcation diagram of the logistic map x → r x (1 – x). Each vertical slice shows the attractor for a specific value of r. The diagram displays period-doubling as r increases, eventually producing chaos. Darker points are visited more frequently.

Barnsley fern created using the chaos game. Natural forms (ferns, clouds, mountains, etc.) may be recreated through an iterated function system (IFS).

Turbulence in the tip vortex from an airplane wing. Studies of the critical point beyond which a system creates turbulence were important for chaos theory, analyzed for example by the Soviet physicist Lev Landau, who developed the Landau-Hopf theory of turbulence. David Ruelle and Floris Takens later predicted, against Landau, that fluid turbulence could develop through a strange attractor, a main concept of chaos theory.

A conus textile shell, similar in appearance to Rule 30, a cellular automaton with chaotic behaviour

The red cars and blue cars take turns to move; the red ones only move upwards, and the blue ones move rightwards. Every time, all the cars of the same colour try to move one step if there is no car in front of it. Here, the model has self-organized in a somewhat geometric pattern where there are some traffic jams and some areas where cars can move at top speed.