Champagne

True Champagne is a strictly regulated product of specific soil, climate, and law

True Champagne is a strictly regulated product of specific soil, climate, and law

While the term is often used generically, legally "Champagne" refers only to sparkling wines produced within a specific region of northeast France under rigid appellation rules. These rules dictate everything from where the grapes are grown (within a 100-mile radius) to the specific vineyard practices used. The wine is almost exclusively a blend of three grapes: Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, and Chardonnay.

The region’s northern climate originally made it difficult to produce high-quality red wines like those in neighboring Burgundy. The grapes struggled to ripen, resulting in thin, highly acidic juices. Paradoxically, this high acidity became the perfect backbone for sparkling wine, turning a geographical disadvantage into a global luxury standard.

Sparkling wine was born of a climate struggle and refined by British engineering

Sparkling wine was born of a climate struggle and refined by British engineering

Contrary to popular myth, the monk Dom Pérignon did not invent sparkling wine; in fact, he originally worked to remove bubbles, which were seen as a defect. The "sparkle" was often an accidental byproduct of the cold French winters, which paused fermentation only for it to restart in the spring once the wine was bottled. This built up pressure that frequently caused bottles to explode, earning it the nickname "the devil’s wine."

The transition from accident to technology happened largely in England. In 1662, scientist Christopher Merret documented the deliberate addition of sugar to trigger a second fermentation. This discovery coincided with British glass-makers developing coal-fired glass strong enough to withstand internal pressure—technology the French did not yet possess. It wasn't until the 19th century that the French fully adopted the méthode champenoise we recognize today.

The "Devil’s Wine" is tamed through a high-pressure secondary fermentation in the bottle

The "Devil’s Wine" is tamed through a high-pressure secondary fermentation in the bottle

The defining characteristic of Champagne is that its carbonation occurs inside the individual bottle you buy, not a large vat. After an initial fermentation, a mixture of yeast and sugar is added to the bottle to trigger a second round of activity. The wine must age for at least 15 months (or three years for vintage bottles) to develop its complex flavor profile.

During this time, the bottles are "riddled"—tilted and turned until the dead yeast (lees) settles in the neck. The neck is then frozen, the cap removed, and the pressure of the CO2 shoots the frozen plug of sediment out (disgorgement). Before the final cork is inserted, a dosage of sugar and wine is added to determine the final sweetness, ranging from bone-dry (Brut) to sweet.

The name is a fiercely guarded legal fortress that excludes even "Champagne, Switzerland"

The name is a fiercely guarded legal fortress that excludes even "Champagne, Switzerland"

The Champagne winemaking community (CIVC) is notoriously litigious in protecting its brand. Under international treaties and EU law, only bottles from the region can use the name. This protection is so absolute that the Swiss village of "Champagne" was forced to stop labeling its own still wines with its own name in 2004, and the EU has even banned terms like "Champagne style" or "Champagne method."

Global compliance varies by political history. The United States allows some "grandfathered" brands to use the term if they include their actual origin (e.g., "California Champagne"), a practice the French find abhorrent. Most recently, in 2021, Russia flipped the script by banning the use of the Russian word for Champagne (shampanskoe) on French imports, reserving the term exclusively for Russian-made sparkling wines.

The label’s fine print reveals whether you are drinking a corporate blend or a farmer's harvest

The label’s fine print reveals whether you are drinking a corporate blend or a farmer's harvest

There are over 19,000 small growers in the region, but the market is dominated by large "Houses." You can identify the producer's business model by two small letters on the label. NM (Négociant manipulant) indicates large houses that buy grapes from many different growers to create a consistent "house style." Most famous brands (like Moët or Veuve Clicquot) are NMs.

Conversely, RM (Récoltant manipulant) signifies "Grower Champagne," where the person who owns the vineyard also makes the wine. These wines are often praised by enthusiasts for expressing "terroir"—the specific character of a single plot of land—rather than the standardized, blended taste aimed for by the major commercial houses.

A glass of Champagne exhibiting the characteristic bubbles associated with the wine

Vineyards in the Champagne region of France

Jean François de Troy's 1735 painting Le Déjeuner d'Huîtres (The Oyster Luncheon) is the first known depiction of Champagne in painting.

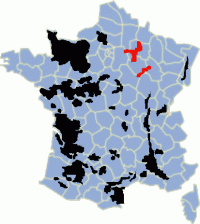

A map of French wine regions, with the Champagne appellation highlighted in red

1915 English magazine illustration of a lady riding a Champagne cork (Lordprice Collection)

Le Remueur: 1889 engraving of the man engaged in the daily task of turning each bottle a fraction

Champagne dosager

Bubbles from rosé Champagne

Champagne uncorking captured via high-speed photography

An Edwardian English advertisement for champagne, listing honours and royal drinkers

Champagne appellation

Most red wine grapes have their color concentrated in the skin, while the juice is much lighter in color.

A Grand Cru blanc de blancs Champagne

Side-by-side comparison of Champagne bottles. (L to R) On ladder: Magnum (1.5 litres), full (0.75 litre), half (0.375 litre), quarter (0.1875 litre). On floor: Balthazar (12 litres), Salmanazar (9 litres), Methuselah (6 litres), Jeroboam (3 litres)

A Champagne cork before usage. Only the lower section, made of top-quality pristine cork, will be in contact with the Champagne.