Carbon cycle

Carbon moves at two speeds: the frantic pulse of life and the tectonic crawl of stone.

Carbon moves at two speeds: the frantic pulse of life and the tectonic crawl of stone.

The carbon cycle isn't a single loop, but a combination of "Fast" and "Slow" cycles. The fast cycle is measured in a human lifespan—carbon moving through plants and animals via eating and breathing. It processes between 10 and 100 billion metric tons of carbon every year, driven primarily by the solar energy that powers photosynthesis.

In contrast, the slow cycle takes millions of years to move carbon through rocks, soil, and the ocean. It involves the chemical weathering of mountains and the subduction of tectonic plates. While the fast cycle handles the day-to-day energy of life, the slow cycle acts as the planet's ultimate ballast, maintaining the long-term chemical equilibrium of the atmosphere.

Biological life is essentially a sophisticated carbon-trading scheme powered by the sun.

Biological life is essentially a sophisticated carbon-trading scheme powered by the sun.

Every living thing is a temporary vessel for carbon. Plants and phytoplankton act as the "entry point," pulling inorganic carbon dioxide from the air or water and using sunlight to forge it into organic sugar. This is the foundation of the global food web; every calorie you consume is essentially a rearranged carbon atom that was once floating in the atmosphere.

When organisms die, "decomposers" return that carbon to the atmosphere, or it becomes buried in soil and peat. This creates a near-perfect closed loop. The beauty of the biological cycle is its efficiency: carbon is rarely wasted, instead being recycled through countless iterations of life, death, and decay over billions of years.

The ocean acts as a massive thermal and chemical sponge that protects the planet at its own expense.

The ocean acts as a massive thermal and chemical sponge that protects the planet at its own expense.

The world's oceans are the largest active carbon reservoir on Earth, holding about 50 times more carbon than the atmosphere. They absorb carbon through two "pumps." The physical pump involves CO2 dissolving directly into the water at the surface, while the biological pump involves marine life consuming carbon and then sinking to the deep ocean when they die, effectively "sequestering" it for centuries.

However, this buffering service comes with a cost. As the ocean absorbs more CO2 to compensate for atmospheric increases, the water becomes more acidic. This "ocean acidification" makes it harder for creatures like corals and shellfish to build their skeletons, potentially collapsing the very biological pumps that keep the cycle in check.

Earth’s long-term habitability is managed by a million-year geological thermostat.

Earth’s long-term habitability is managed by a million-year geological thermostat.

Without a way to regulate CO2, Earth would likely have spiraled into a permanent greenhouse state like Venus or a frozen wasteland like Mars. The "silicate-carbonate cycle" provides this stability. When the planet gets too hot, increased rainfall leaches minerals from rocks that react with CO2, scrubbing it from the air and washing it into the sea to become limestone.

When the planet cools, this weathering slows down, allowing volcanic activity to slowly replenish atmospheric CO2 levels. This feedback loop is incredibly slow—taking hundreds of thousands of years to correct a temperature spike—but it is the primary reason Earth has remained within the narrow temperature range required for liquid water and life for billions of years.

Industrialization has short-circuited the cycle by moving carbon from deep storage into the sky.

Industrialization has short-circuited the cycle by moving carbon from deep storage into the sky.

Humans have fundamentally altered the "budget" of the carbon cycle. By burning fossil fuels, we are taking carbon that the slow cycle spent 300 million years burying underground and injecting it into the fast cycle in a matter of decades. We are essentially "mining time," releasing ancient solar energy and its accompanying carbon at a rate the natural sinks cannot match.

Because the slow cycle (rock weathering) cannot speed up to meet this sudden influx, the excess carbon accumulates in the atmosphere and oceans. This creates a bottleneck: we are adding carbon to the system faster than the planet's "drains" can remove it, shifting the entire global climate out of the equilibrium that has defined the Holocene epoch.

---

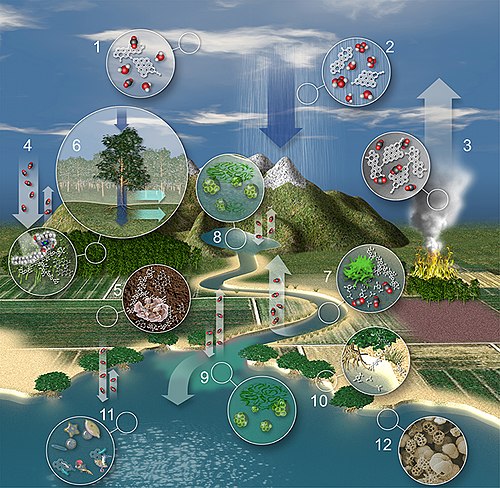

Carbon cycle schematic showing the movement of carbon between land, atmosphere, and oceans in billions of tons (gigatons) per year. Yellow numbers are natural fluxes, red are human contributions, and white are stored carbon. The effects of the slow (or deep) carbon cycle, such as volcanic and tectonic activity are not included.

CO2 concentrations over the last 800,000 years as measured from ice cores (blue/green) and directly (black)

Amount of carbon stored in Earth's various terrestrial ecosystems, in gigatonnes.

A portable soil respiration system measuring soil CO2 flux.

Diagram showing relative sizes (in gigatonnes) of the main storage pools of carbon on Earth. Cumulative changes (thru year 2014) from land use and emissions of fossil carbon are included for comparison.

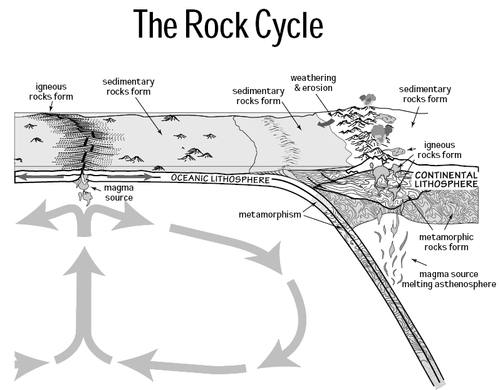

The slow (or deep) carbon cycle operates through rocksThe fast carbon cycle operates through the biosphere, see diagram at start of article ↑

Where terrestrial carbon goes when water flows

How carbon moves from inland waters to the ocean Carbon dioxide exchange, photosynthetic production and respiration of terrestrial vegetation, rock weathering, and sedimentation occur in terrestrial ecosystems. Carbon transports to the ocean through the land-river-estuary continuum in the form of organic carbon and inorganic carbon. Carbon exchange at the air-water interface, transportation, transformation and sedimentation occur in oceanic ecosystems..

Flow of carbon through the open ocean

Comparison of how virus regulate the carbon cycle in terrestrial ecosystems (left) and in marine ecosystems (right). Arrows show the roles viruses play in the traditional food web, the microbial loop and the carbon cycle. Light green arrows represent the traditional food web, white arrows represent the microbial loop, and white dotted arrows represent the contribution rate of carbon produced by viral lysing of bacteria to the ecosystem dissolved organic carbon (DOC) pool. Freshwater ecosystems are regulated in a manner similar to marine ecosystems, and are not shown separately. The microbial loop is an important supplement to the classic food chain, wherein dissolved organic matter is ingested by heterotrophic "planktonic" bacteria during secondary production. These bacteria are then consumed by protozoa, copepods and other organisms, and eventually returned to the classical food chain.

Movement of oceanic plates—which carry carbon compounds—through the mantle

Carbon outgassing through various processes

Carbon is tetrahedrally bonded to oxygen

Knowledge about carbon in the core can be gained by analysing shear wave velocities

Emissions of CO2 have been caused by different sources ramping up one after the other (Global Carbon Project)