California gold rush

A carpenter’s chance discovery at a sawmill ignited the largest mass migration in American history.

A carpenter’s chance discovery at a sawmill ignited the largest mass migration in American history.

In January 1848, James W. Marshall spotted shiny flakes in the tailrace of a sawmill he was building for John Sutter. Though they tried to keep it a secret, the news leaked, triggering a global frenzy. By 1849, approximately 300,000 "forty-niners" had descended on California from across the United States, China, Europe, and Latin America, traveling via grueling overland trails or dangerous sea voyages around Cape Horn.

This wasn't just a local event; it was a demographic earthquake. San Francisco transformed from a tiny hamlet of 200 residents into a booming metropolis of 36,000 in just two years. The sheer speed of the influx forced California to bypass the typical "territory" phase of U.S. expansion, leaping directly into statehood by 1850.

The real fortunes were made by "mining the miners" rather than digging for gold.

The real fortunes were made by "mining the miners" rather than digging for gold.

While the image of the lone prospector striking it rich persists, the majority of miners barely broke even after accounting for the astronomical cost of living. In the "gold fields," a single egg could cost the equivalent of $30 in today's money. The true, lasting wealth of the era was captured by merchants, real estate moguls, and transport tycoons who provided the infrastructure for the rush.

Famous brands like Levi Strauss & Co. and Studebaker found their footing by serving the needs of the influx. These entrepreneurs realized that while gold was a gamble, the need for sturdy pants, shovels, and reliable transportation was a certainty. This economic shift laid the foundation for California’s future as a global agricultural and industrial powerhouse.

The wealth of the rush was built on the systematic displacement and state-sponsored genocide of Indigenous people.

The wealth of the rush was built on the systematic displacement and state-sponsored genocide of Indigenous people.

The Gold Rush was a catastrophe for California’s Native American population. Before the discovery, there were roughly 150,000 Indigenous people in the region; by 1870, fewer than 30,000 remained. Miners viewed the native population as obstacles to progress, leading to widespread forced labor, starvation, and direct "expeditions" of extermination funded by the state government.

This era also saw the rise of intense nativism. As easily accessible gold vanished, white miners turned their frustration toward foreign competitors. The state legislature passed the Foreign Miners' Tax, specifically targeting Chinese and Latin American prospectors, cementing a racial hierarchy in the West that would persist for generations.

Mining evolved from simple hand tools to high-pressure water cannons that permanently scarred the landscape.

Mining evolved from simple hand tools to high-pressure water cannons that permanently scarred the landscape.

In the early days, "placer" mining required nothing more than a pan and a stream to find loose gold. However, as the surface gold was depleted, operations became industrial and destructive. By the 1850s, "hydraulic mining" became the standard—using high-pressure jets of water to blast away entire hillsides to reach the ancient gold-bearing gravel beneath.

The environmental fallout was unprecedented. The resulting "slickens" (silt and debris) choked rivers, caused massive flooding in the Central Valley, and destroyed downstream farmland. This eventually led to the 1884 Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Co. decision, one of the first major environmental rulings in U.S. history, which effectively ended large-scale hydraulic mining in the Sierras.

Image from Wikipedia

1855 illustration of James W. Marshall, discoverer of gold at Sutter's Mill

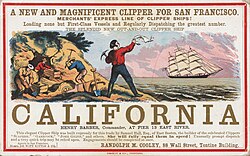

Advertisement about sailing to California, c. 1850

Merchant ships fill San Francisco Bay, 1850–51.

![Independent Gold Hunter on His Way to California, c. 1850[b]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/26/Independent_Gold_Hunter_on_His_Way_to_California.jpg/250px-Independent_Gold_Hunter_on_His_Way_to_California.jpg)

Independent Gold Hunter on His Way to California, c. 1850[b]

Joaquín Murrieta, called the "Robin Hood of California", was a notorious outlaw during the gold rush.

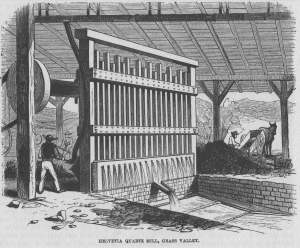

Replica of a horse-powered Chilean mill which Chileans introduced to California during the gold rush

Forty-niner panning for gold

Sluice for separation of gold from dirt using water

Excavating a riverbed after the water has been diverted

Crushing quartz ore prior to washing out gold

California gold miners with long tom, c. 1850–1852

Mining on the American River near Sacramento, c. 1852

Californio miner processing ore, c. 1862

Excavating a gravel bed with jets, c. 1863