Black hole

Gravity so extreme it creates a one-way exit from the universe

Gravity so extreme it creates a one-way exit from the universe

A black hole is not a "hole" in the traditional sense, but a region of space where matter has been packed so densely that gravity overpowers everything else. This creates an event horizon—a mathematical boundary representing the "point of no return." Once anything, including light, crosses this threshold, the escape velocity required to leave exceeds the speed of light, making exit physically impossible under our current understanding of the universe.

Because light cannot escape, black holes are inherently invisible. They do not have a surface like a planet or a star; instead, they represent a profound warping of spacetime. To an outside observer, an object falling toward the event horizon would appear to slow down and redden due to gravitational time dilation, eventually "freezing" at the edge and fading away, never actually being seen to cross over.

Only the most massive stars leave behind these gravitational "corpses"

Only the most massive stars leave behind these gravitational "corpses"

Black holes are the final evolutionary stage of stars at least 20 times more massive than our Sun. When such a star exhausts its nuclear fuel, it can no longer support its own weight against gravity. The core collapses inward with such violence that it triggers a supernova explosion, blowing off the outer layers while the remaining core shrinks into a volume of zero size and infinite density.

This process is governed by the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit, which dictates that if a collapsed stellar core is heavy enough, no known force in nature can stop it from becoming a black hole. While our Sun will eventually become a white dwarf, it lacks the necessary mass to ever collapse into a black hole, ensuring the solar system is safe from such a fate.

We "see" the invisible by watching the violent tantrums of nearby matter

We "see" the invisible by watching the violent tantrums of nearby matter

While the black hole itself emits no light, the area immediately surrounding it is one of the brightest and most violent environments in the cosmos. As gas and dust from nearby stars are pulled toward the event horizon, they form an "accretion disk." Friction and gravity heat this material to millions of degrees, causing it to glow brilliantly in X-rays and radio waves before it is swallowed.

In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope provided the first direct visual evidence of this phenomenon by capturing the "shadow" of the supermassive black hole in the galaxy M87. We also detect black holes through their gravitational influence; by tracking stars orbiting seemingly empty patches of space at incredible speeds, astronomers can calculate the massive, invisible weight of the object tethering them.

Supermassive black holes act as the invisible architects of entire galaxies

Supermassive black holes act as the invisible architects of entire galaxies

Nearly every large galaxy, including our own Milky Way, harbors a supermassive black hole at its center, containing millions or even billions of times the mass of the Sun. These giants are not merely passive consumers of matter; they play a critical role in galactic evolution. The energy released by their "feeding"—often seen as massive jets of plasma shooting out at near-light speed—can heat up intergalactic gas and regulate the rate at which new stars are born.

The origin of these monsters remains a major cosmological mystery. They appear to have existed very early in the universe's history, leading some scientists to wonder if they formed from the collapse of massive gas clouds or if they grew rapidly through successive mergers. Regardless of their birth, the health and structure of a galaxy are inextricably linked to the behavior of its central black hole.

The "singularity" represents a fundamental breakdown in the laws of physics

The "singularity" represents a fundamental breakdown in the laws of physics

At the very center of a black hole lies the singularity, a point where general relativity predicts density becomes infinite and the volume becomes zero. At this scale, the math we use to describe the universe fails. This creates a "clash of titans": General Relativity (the physics of the very large) and Quantum Mechanics (the physics of the very small) provide contradictory answers about what happens to information and matter at the core.

Stephen Hawking famously proposed that black holes aren't "perfectly" black; due to quantum effects near the event horizon, they should emit a faint glow known as Hawking Radiation. Over unimaginably long timescales, this radiation causes the black hole to lose mass and eventually evaporate. This leads to the "Information Paradox"—the question of whether the information about what fell into the black hole is lost forever or somehow preserved, a debate that remains at the bleeding edge of modern physics.

An image of the core region of Messier 87, a supermassive black hole, processed from a sparse array of radio telescopes known as the EHT with colors indicating brightness temperature.

The first simulated image of a black hole, created by Jean-Pierre Luminet in 1978 and featuring the characteristic shadow, photon sphere, and lensed accretion disk. The disk is brighter on one side due to the Doppler beaming.

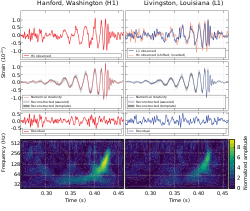

The first detection of gravitational waves, imaged by LIGO observatories in Hanford Site, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana

Image by the Event Horizon Telescope of the supermassive black hole in the center of Messier 87

An artistic depiction of a black hole and its features

Relativistic jets from the supermassive black hole in Centaurus A extend perpendicularly from the galaxy.

Visualization of a black hole with an orange accretion disk. The parts of the disk circling over and under the hole are actually gravitationally lensed from the back side of the black hole.

Since particles in a black hole's accretion disk must orbit at or outside the ISCO, astronomers can observe the properties of accretion disks to determine black hole spins.

Gas cloud being ripped apart by black hole at the centre of the Milky Way (observations from 2006, 2010 and 2013 are shown in blue, green and red, respectively)

The active galactic nucleus of galaxy Centaurus A in X-ray light, believed to be powered by a supermassive black hole (centre) and surrounded by x-ray binaries (blue dots).

An artist's impression (top) of a supermassive black hole tidally deforming a star based on observations from the Chandra X-ray observatory and the European Southern Observatory.

An M87* image with superimposed lines representing the magnitude and direction of polarization.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way

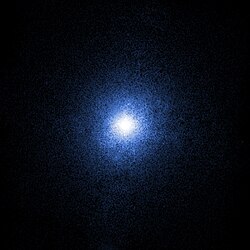

A Chandra X-Ray Observatory image of Cygnus X-1, which was the first strong black hole candidate discovered

Detection of unusually bright X-ray flare from Sagittarius A*, a black hole in the centre of the Milky Way galaxy on 5 January 2015