Black Death

The pandemic eradicated half of Europe’s population and stalled demographic growth for two centuries.

The pandemic eradicated half of Europe’s population and stalled demographic growth for two centuries.

The Black Death (1346–1353) remains one of the most lethal events in human history, claiming as many as 50 million lives. In Europe alone, the mortality rate reached roughly 50%, a catastrophic loss that restructured the continent's social and economic foundations. The Middle East suffered similarly, losing an estimated one-third of its population.

The sheer scale of the disaster created a demographic "trough" that took generations to exit. Because the plague recurred in smaller waves throughout the Late Middle Ages, the European population did not return to its pre-1347 levels until the 16th century. This persistent threat fundamentally altered religious life, labor markets, and the course of Western history.

The term "Black Death" is a retrospective label that didn't enter the English language until the 18th century.

The term "Black Death" is a retrospective label that didn't enter the English language until the 18th century.

During the actual outbreak, victims and writers didn't call it the "Black Death." They referred to it in Latin as pestis (pestilence) or magna mortalitas (the Great Mortality). English speakers of the time called it the "Great Death" or simply "the Plague." The "black" moniker likely stems from a 16th-century Scandinavian translation of the Latin mors atra, which originally referred to the "dark" or "gloomy" prognosis of the disease rather than the color of the symptoms.

The name "Black Death" only became the standard English term in the 1750s. While some early writers used the phrase to describe the fatal astrological conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter—blamed for the "great pestilence in the air"—it took centuries for the term to become the definitive proper name for the 14th-century catastrophe.

DNA evidence from medieval tooth pulp has definitively ended the debate over the pandemic's biological cause.

DNA evidence from medieval tooth pulp has definitively ended the debate over the pandemic's biological cause.

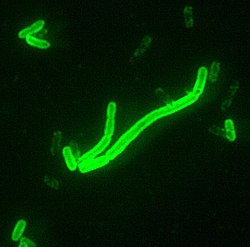

For decades, historians argued over whether the Black Death was truly the plague or a different viral pathogen. In 2010 and 2011, researchers used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques to extract DNA from the tooth sockets of skeletons in medieval mass graves. The results were unambiguous: the bacterium Yersinia pestis was the causative agent.

Genomic sequencing shows that the medieval strain is the ancestor of almost all modern plague strains, including the one that hit Madagascar in 2013. This bacterium thrives by obstructing the midgut of fleas; as the flea starves, it bites hosts aggressively and regurgitates bacteria into the wound, creating a highly efficient transmission cycle between rodents and humans.

The plague’s entry into Europe was facilitated by a 1347 siege and the hyper-connectivity of Genoese trade.

The plague’s entry into Europe was facilitated by a 1347 siege and the hyper-connectivity of Genoese trade.

While the plague's deep origins are traced to the Tian Shan mountains of Kyrgyzstan in the 1330s, its "Patient Zero" moment for Europe occurred in Crimea. During the Siege of Kaffa, the Golden Horde army reportedly experienced an outbreak and introduced the disease to the Genoese trading port. When Genoese ships fled the siege, they carried infected rats and fleas across the Mediterranean.

The disease followed the era’s most lucrative trade routes, hitting Constantinople, Sicily, and the Italian Peninsula in rapid succession. This highlights a grim irony of the era: the same commercial infrastructure that brought prosperity and silk to Europe provided the high-speed rail for its near-destruction.

Scientists now believe the plague spread "person-to-person" to account for its terrifying speed.

Scientists now believe the plague spread "person-to-person" to account for its terrifying speed.

The traditional "rat-flea-human" model has a flaw: it is too slow to explain how the Black Death raced across Europe. Modern mathematical modeling and archaeological records suggest that while rats were the initial reservoir, the rapid inland spread was likely driven by human-to-human transmission. This occurred either as pneumonic plague (spread through the air) or via human parasites like body lice and "human fleas."

In Northern Europe, where the Oriental rat flea struggles to survive the cold, the human-to-human theory is particularly compelling. Excavations in London have supported the "pneumonic hypothesis," suggesting that once the plague reached a crowded city, it no longer needed rats to jump from one household to the next.

Medieval cities were ecological powder kegs where filth and proximity invited disaster.

Medieval cities were ecological powder kegs where filth and proximity invited disaster.

The hygiene of the 14th century offered no defense against a flea-borne pathogen. Urban centers were notoriously congested and lacked waste management; in Paris, several streets were literally named after human excrement (rue Merde). Livestock—pigs, chickens, and horses—roamed the same narrow alleys as humans, creating a perfect environment for parasites to flourish.

Because germ theory was centuries away, the leading medical minds of the day blamed the stars or "miasma" (bad air). Without an understanding of the microscopic world, people were powerless to stop the vectors of the disease. The filth of the medieval city didn't just cause the plague; it acted as a massive amplifier for it.

The spread of the Black Death in Europe and the Near East (1346–1353)

Yersinia pestis (200 × magnification), the bacterium that causes plague

The Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) engorged with blood. This species of flea is the primary vector for the transmission of Yersinia pestis, the organism responsible for spreading bubonic plague in most plague epidemics. Both male and female fleas feed on blood and can transmit the infection.

Skeletons in a mass grave from 1720 to 1721 in Martigues, near Marseille in southern France, yielded molecular evidence of the orientalis strain of Yersinia pestis, the organism responsible for bubonic plague. The second pandemic of bubonic plague was active in Europe from 1347, the beginning of the Black Death, until 1750.

A hand showing how acral gangrene of the fingers due to bubonic plague causes the skin and flesh to die and turn black

An inguinal bubo on the upper thigh of a person infected with bubonic plague. Swollen lymph nodes (buboes) often occur in the neck, armpit and groin (inguinal) regions of plague victims.

Inspired by the Black Death, The Dance of Death, or Danse Macabre, an allegory on the universality of death, was a common painting motif in the late medieval period.

Citizens of Tournai bury plague victims

Jews being burned at the stake in 1349. Miniature from a 14th-century manuscript Antiquitates Flandriae by Gilles Li Muisis

Pieter Bruegel's The Triumph of Death reflects the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague, which devastated medieval Europe.

The Great Plague of London, in 1665, killed up to 100,000 people.

A plague doctor and his typical apparel during the 17th-century outbreak

Worldwide distribution of plague-infected animals, 1998