Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau was a radical "total work of art" that erased the boundary between a painting on a wall and the wall itself.

Art Nouveau was a radical "total work of art" that erased the boundary between a painting on a wall and the wall itself.

The movement’s primary objective was to dismantle the traditional hierarchy that placed fine arts (painting and sculpture) above applied arts (furniture, textiles, and metalwork). Proponents sought a Gesamtkunstwerk—a "total work of art"—where every element of an interior, from the architecture and the wallpaper to the silverware and the jewelry, was unified by a single aesthetic. It was a rebellion against 19th-century academicism and the cluttered, "historical" styles of the past.

This philosophy was driven by leading theorists like Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and John Ruskin, who argued that function should define form and that the decorative arts should be spiritually uplifting. By treating a chair or a subway entrance with the same creative gravity as a canvas, Art Nouveau designers aimed to harmonize the modern human environment with the rhythms of the natural world.

The style weaponized the "whiplash line" to translate organic growth into industrial materials like iron and glass.

The style weaponized the "whiplash line" to translate organic growth into industrial materials like iron and glass.

While Art Nouveau was deeply inspired by the sinuous curves of plants and flowers, it was not merely an imitation of nature. It used asymmetry and "whiplash lines"—sudden, energetic curves—to create a sense of dynamism and movement. This visual language was uniquely enabled by modern materials. For the first time, iron and glass were not just hidden structural necessities but were exposed and molded into unusual, organic forms that allowed for larger, light-filled open spaces.

In Brussels, Victor Horta pioneered this approach by using slender iron columns that branched out like tree trunks to support glass skylights. Similarly, Hector Guimard’s iconic Paris Métro entrances transformed industrial cast iron into fluid, vine-like structures. This marriage of the biological and the industrial gave the movement its "modern" edge, separating it from the purely handcrafted Arts and Crafts movement that preceded it.

The movement’s DNA was spliced from British craftsmanship, French rationalism, and a feverish obsession with Japanese woodblock prints.

The movement’s DNA was spliced from British craftsmanship, French rationalism, and a feverish obsession with Japanese woodblock prints.

Art Nouveau was a global synthesis of several distinct influences. It grew from the British Arts and Crafts movement’s emphasis on quality and nature, but it was also shaped by "Japonism"—a European craze for Japanese woodblock prints. Artists like Gustav Klimt and Aubrey Beardsley adopted the flattened perspectives, stylized floral patterns, and bold outlines of ukiyo-e prints to create a new graphic language that felt both exotic and contemporary.

Simultaneously, French rationalism provided the intellectual backbone. Theorists like Viollet-le-Duc advocated for the use of "the means and knowledge given to us by our times." This encouraged architects to stop copying the Greeks and Romans and instead invent a new architecture that reflected the needs of the 1890s. The result was a style that felt ancient and organic, yet was fueled by the latest printing technologies and engineering possibilities.

As a global chameleon, Art Nouveau adopted dozens of local names while fueling national identities across Europe.

As a global chameleon, Art Nouveau adopted dozens of local names while fueling national identities across Europe.

Art Nouveau was rarely called by that name outside of France and Belgium. In Germany and Scandinavia, it was Jugendstil ("Youth Style"); in Italy, Stile Liberty; in Spain, Modernisme; and in Austria, the Secession style. Each region adapted the movement to its own cultural needs. In many cases, it became a tool for political identity, particularly in cities like Barcelona, Helsinki, and Glasgow that were looking to establish artistic independence from traditional imperial capitals.

The style’s rapid spread was facilitated by a new explosion in mass media. High-quality art magazines like The Studio and Jugend featured color lithographs and photographs that allowed designers in Tokyo or New York to see and adapt what was happening in Brussels or Paris almost instantly. This made Art Nouveau one of the first truly international "viral" aesthetics of the modern age.

Though extinguished by the First World War, Art Nouveau’s focus on integrated design set the stage for 20th-century Modernism.

Though extinguished by the First World War, Art Nouveau’s focus on integrated design set the stage for 20th-century Modernism.

By 1914, the movement had largely exhausted its creative energy. Its elaborate, hand-finished details were expensive to produce, and the onset of World War I shifted the global focus toward the stark efficiency of industrial production. In the 1920s, the fluid curves of Art Nouveau were replaced by the geometric rigidity of Art Deco and the functionalism of the Bauhaus.

However, the movement's legacy survived in the core tenets of modern design: the idea that the "minor arts" deserve serious attention and that an object’s form should be dictated by its function and materials. After decades of being dismissed as overly decorative "noodle style," Art Nouveau was rediscovered in the late 1960s, recognized finally as a necessary bridge between the ornate past and the functional future.

Image from Wikipedia

Red House in Bexleyheath (London) by William Morris and Philip Webb (1859)

Japanese woodblock print by Utagawa Kunisada (1850s)

The Peacock Room by James McNeill Whistler (1876–77), now in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

William Morris printed textile design (1883)

Swan, rush and iris wallpaper design by Walter Crane (1883)

Hankar House by Paul Hankar (1893)

Façade of the Hôtel Tassel by Victor Horta (1892–93)

Stairway of the Hôtel Tassel

Villa Bloemenwerf by Henry van de Velde (1895)

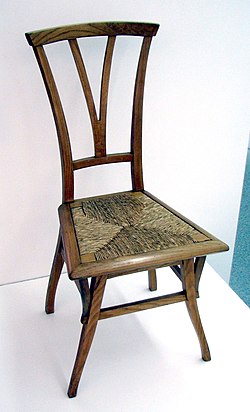

Chair by Van de Velde for the Villa Bloemenwerf (1895)

Siegfried Bing invited artists to show modern works in his new Maison de l'Art Nouveau (1895).

The Maison de l'Art Nouveau gallery of Siegfried Bing (1895)

Poster by Félix Vallotton for the new Maison de l'Art Nouveau (1896)

Gateway of the Castel Béranger by Hector Guimard (1895–1898)