Aristotle

A royal physician’s son who became the "mind" of Plato’s Academy before building his own empirical empire.

A royal physician’s son who became the "mind" of Plato’s Academy before building his own empirical empire.

Born in 384 BC in Stagira, Aristotle was the son of the personal physician to the King of Macedon. This medical lineage likely sparked his lifelong obsession with biology and the "stuff" of the world. At 18, he joined Plato’s Academy in Athens, remaining for 20 years as a student and teacher. Plato famously dubbed him the "mind of the school," yet Aristotle eventually broke from his mentor's idealistic focus on abstract "Forms" to champion a more grounded, observational approach to reality.

After Plato’s death, Aristotle’s path took a political turn when he was hired by Philip II of Macedon to tutor the young Alexander the Great. He taught the future conqueror ethics and politics, though their relationship eventually cooled over Alexander’s administrative styles. Returning to Athens, Aristotle founded the Lyceum, a school known as the "Peripatetic" school because he and his students often discussed philosophy while walking through the colonnades (peripatos).

He grounded Plato’s abstract "Forms" into the physical world through the union of matter and structure.

He grounded Plato’s abstract "Forms" into the physical world through the union of matter and structure.

While Plato believed that "true reality" existed in a separate realm of perfect ideas, Aristotle brought philosophy down to earth. He developed hylomorphism, the theory that every individual thing is a composite of matter (the physical "stuff") and form (the internal structure or essence that makes it what it is). To Aristotle, there is no "Ideal Apple" in a distant dimension; the "Appleness" exists specifically inside each physical apple.

This "moderate realism" allowed Aristotle to categorize the world with scientific precision. He argued that universals—the qualities that things share—are only real when they are "instantiated" in physical objects. This shift in perspective shifted the goal of human knowledge from pure contemplation of the divine to the systematic study of biology, physics, and nature.

He systematized human thought into the "Organon," creating a logical framework that went unchallenged for 2,000 years.

He systematized human thought into the "Organon," creating a logical framework that went unchallenged for 2,000 years.

Aristotle is credited with the first systematic study of logic. His works, later collected as the Organon ("The Tool"), introduced the Syllogism—a method of logical argument where a conclusion is drawn from two premises (e.g., All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal). This became the standard for Western reasoning until the 19th century; Immanuel Kant even remarked that logic had essentially reached its "completion" with Aristotle.

His logic was not just about words, but about Demonstration. For Aristotle, true knowledge required understanding the causes of things. By applying syllogistic reasoning to the natural world, he laid the groundwork for the scientific method, emphasizing that we understand a thing only when we know why it cannot be any other way.

He defined existence as a constant transition from potentiality to actuality.

He defined existence as a constant transition from potentiality to actuality.

To explain how the world is always moving and changing, Aristotle introduced the concepts of Potentiality (dynamis) and Actuality (entelecheia). A seed is not yet a tree, but it is "potentially" a tree. Change is simply the process of that potential becoming actual. This framework allowed him to explain everything from the growth of a plant to the development of a human soul.

This focus on "becoming" extended to his ethics. He didn't see "virtue" as a list of rules, but as a potential that humans must actualize through habit. This "virtue ethics" suggests that by repeatedly making the right choices, we transform our potential for goodness into a permanent state of character. This practical approach to living well remains a major pillar of contemporary moral philosophy.

His "lost" lecture notes became the primary operating system for Medieval Christian and Islamic thought.

His "lost" lecture notes became the primary operating system for Medieval Christian and Islamic thought.

Surprisingly, we do not possess any of the polished books Aristotle wrote for public consumption; they were lost to history. The 30 or so treatises we have today are actually his "esoteric" works—internal lecture notes, diagrams, and research files intended for his students at the Lyceum. These dense, difficult texts were rediscovered and edited centuries after his death.

Despite their raw state, these notes dominated the intellectual world for over a millennium. Medieval Muslim scholars revered him as "The First Teacher," and Christian theologians like Thomas Aquinas referred to him simply as "The Philosopher." His influence was so total that his views on physics and the cosmos weren't systematically replaced until the Enlightenment and the rise of classical mechanics.

*

Image from Wikipedia

School of Aristotle in Mieza, Macedonia, Greece

"Aristotle tutoring Alexander" (1895) by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

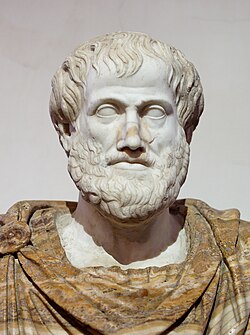

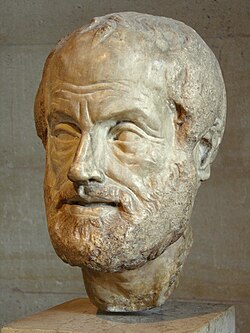

Portrait bust of Aristotle; an Imperial Roman (1st or 2nd century AD) copy of a lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos

Plato (left) and Aristotle in Raphael's 1509 fresco, The School of Athens. Aristotle holds his Nicomachean Ethics and gestures to the earth, representing his view in immanent realism, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, indicating his Theory of Forms, and holds his Timaeus.

Plato's forms exist as universals, like the ideal form of an apple. For Aristotle, both matter and form belong to the individual thing (hylomorphism).

Aristotle argued that a capability like playing the flute could be acquired — the potential made actual — by learning.

The four classical elements (fire, air, water, earth) of Empedocles and Aristotle illustrated with a burning log. The log releases all four elements as it is destroyed.

Aristotle's laws of motion. In Physics he states that objects fall at a speed proportional to their weight and inversely proportional to the density of the fluid they are immersed in. This is a correct approximation for objects in Earth's gravitational field moving in air or water.

Aristotle argued by analogy with woodwork that a thing takes its form from four causes: in the case of a table, the wood used (material cause), its design (formal cause), the tools and techniques used (efficient cause), and its decorative or practical purpose (final cause).

Aristotle noted that the ground level of the Aeolian islands changed before a volcanic eruption.

Among many pioneering zoological observations, Aristotle described the reproductive hectocotyl arm of the octopus (bottom left).

Aristotle inferred growth laws from his observations on animals, including that brood size decreases with body mass, whereas gestation period increases.

Aristotle recorded that the embryo (fetus pictured) of a dogfish was attached by a cord to a kind of placenta (the yolk sac), like a higher animal; this formed an exception to the linear scale from highest to lowest.

Aristotle proposed a three-part structure for souls of plants, animals, and humans, making humans unique in having all three types of soul.