Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism is defined by an analytical method that views the world through systematic classification and purposeful causation.

Aristotelianism is defined by an analytical method that views the world through systematic classification and purposeful causation.

Rather than focusing on abstract ideals, Aristotelians use a combination of deductive logic and inductive observation to study everything from biology to politics. The tradition is anchored by the "four causes," a framework for answering why things exist. Most distinctive is the concept of teleology—the belief that all natural entities have an inherent purpose or "end" (telos) they are striving to achieve.

This method created a unified system where the social sciences were treated under natural law. Because the school of thought is so vast, spanning ethics, aesthetics, and physics, modern "Aristotelians" may share little in common regarding actual content; what binds them is a shared starting point in Aristotle's distinctive positions and his commitment to virtue-based ethics.

The survival of the Aristotelian corpus was secured by Islamic polymaths who evolved Greek logic into a global intellectual foundation.

The survival of the Aristotelian corpus was secured by Islamic polymaths who evolved Greek logic into a global intellectual foundation.

While much of Aristotle’s work was lost to Western Europe after the fall of Rome, it flourished in the Islamic Golden Age. In Baghdad’s House of Wisdom, scholars like Al-Kindi and Hunayn ibn Ishaq translated the corpus into Arabic. Philosophers such as Al-Farabi (the "Second Teacher") and Avicenna synthesized these texts with Islamic theology, creating a sophisticated philosophical framework known as Avicennism.

Later, in Muslim Spain, Averroes produced exhaustive commentaries that sought to return to a "pure" Aristotle, stripped of later Neoplatonic additions. His work was so influential that it eventually sparked a radical intellectual revolution in the Latin West, leading to a school of thought known as Averroism that challenged traditional Christian interpretations.

Medieval scholars fused pagan logic with monotheistic theology to create the rigid intellectual architecture of Scholasticism.

Medieval scholars fused pagan logic with monotheistic theology to create the rigid intellectual architecture of Scholasticism.

The reintroduction of Aristotle to Western Europe in the 12th century was initially met with suspicion and even formal bans by the Catholic Church, which viewed his natural philosophy as heterodox. However, scholars like Albertus Magnus and his student Thomas Aquinas successfully "baptized" Aristotle. Aquinas adopted Aristotle's views on motion, cosmology, and sense perception, weaving them into a systematic Catholic theology known as Thomism.

This synthesis wasn't limited to Christianity; Moses Maimonides performed a similar feat for Judaism, basing his Guide for the Perplexed on Aristotelian logic. This era of "Scholasticism" turned Aristotle’s writings into the standard curriculum for European universities, making his logic the "handmaid of theology" for centuries.

Contemporary Aristotelianism has pivoted from explaining the mechanics of the universe to defining the "good life" through virtue ethics.

Contemporary Aristotelianism has pivoted from explaining the mechanics of the universe to defining the "good life" through virtue ethics.

While modern science eventually rejected Aristotle’s physics and biology, his ethical framework saw a major 20th-century revival. Philosophers like Alasdair MacIntyre and Martha Nussbaum moved away from his outdated metaphysical claims to focus on "Virtue Ethics." They argue that human excellence isn't about following abstract rules (like Kant) or calculating utility (like Bentham), but about developing character traits within a community.

In this modern "Revolutionary Aristotelianism," the state is viewed not just as a legal entity but as a "public sphere" constituted by the virtuous activity of its citizens. This shift treats philosophy as a practical tool for living well, suggesting that the highest human goods are actualized through participation in shared social practices rather than individualistic accumulation.

Aristotle by Francesco Hayez, 1811

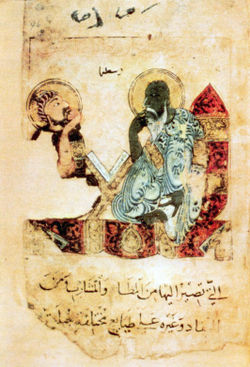

A medieval Arabic representation of Aristotle teaching a student.

Aristotle, holding his Ethics (detail from The School of Athens)