American Civil War

The conflict was fundamentally an existential battle over the preservation and expansion of African American slavery.

The conflict was fundamentally an existential battle over the preservation and expansion of African American slavery.

While late-19th-century "Lost Cause" narratives attempted to frame the war as a dispute over "states' rights," contemporary historians and the seceding states’ own documents confirm that slavery was the central cause. Southern states feared that the election of Abraham Lincoln—who opposed the expansion of slavery into Western territories—marked the beginning of the end for their agrarian, slave-based economy. To the South, slavery was not just a labor system but "the greatest material interest of the world."

The political friction centered on whether new states entering the Union would be "free" or "slave," as this determined the balance of power in Congress. As Northern abolitionist sentiment grew and the North’s population outstripped the South’s, Southern leaders felt secession was the only way to protect their constitutional right to hold property in humans. The North’s refusal to allow secession was driven by a different brand of nationalism: the belief that the Union was a permanent, binding contract that could not be dissolved by a minority vote.

Lincoln’s 1860 victory forced a collision between constitutional permanence and revolutionary secession.

Lincoln’s 1860 victory forced a collision between constitutional permanence and revolutionary secession.

Abraham Lincoln’s election triggered an immediate crisis, despite his initial promise not to interfere with slavery where it already existed. Seven Deep South states seceded before he even took office, seizing federal forts and assets within their borders. This four-month "lame duck" period allowed the Confederacy to organize a government and military, while the outgoing Buchanan administration dithered, arguing that while secession was illegal, the federal government lacked the power to stop it by force.

Lincoln’s inaugural stance was legally rigid: he declared secession "legally void" and the Union "perpetual." He refused to recognize the Confederacy as a legitimate nation, viewing it instead as a collection of states in rebellion. This led to a diplomatic stalemate; Lincoln would not negotiate with Confederate delegates because doing so would grant them the status of a sovereign power, which he was determined to deny.

The war began as a calculated chess match where the North forced the South to fire the first shot.

The war began as a calculated chess match where the North forced the South to fire the first shot.

The standoff at Fort Sumter in South Carolina was the war's first great strategic test. Low on supplies, the Union garrison was a symbol of federal authority in the heart of the rebellion. Lincoln devised a "win-win" scenario: he informed South Carolina he would send an unarmed ship with food—but no ammunition—to the fort. If the South allowed the ship through, the Union maintained its presence; if the South fired, they would be branded the aggressors in a war to starve a garrison.

On April 12, 1861, the Confederacy chose to open fire, bombarding the fort into surrender. This act of aggression galvanized Northern public opinion, transforming a political dispute into a military crusade. Following the attack, four more states—including Virginia—seceded, and both sides saw a massive surge in volunteer recruitment, fueled by the naive belief that the conflict would be short and relatively bloodless.

The Union transitioned from a war of preservation to a war of social revolution and total exhaustion.

The Union transitioned from a war of preservation to a war of social revolution and total exhaustion.

By 1863, the nature of the war shifted from a traditional military struggle to a "total war" aimed at destroying the South’s ability to function. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation fundamentally changed the Union’s war goals; it was no longer just about restoring the map, but about a "new birth of freedom." This move also served a diplomatic purpose, making it politically impossible for anti-slavery European powers like Britain or France to intervene on the side of the Confederacy.

The military tide turned in the summer of 1863 with simultaneous Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the latter of which split the Confederacy in two. Under General Ulysses S. Grant, the Union began a relentless campaign of attrition, while William Tecumseh Sherman’s "March to the Sea" destroyed the South’s infrastructure and psychological will. By the time Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox in 1865, the South was economically ruined, its social order was upended, and 4 million people were no longer property, but citizens.

The Civil War served as a brutal laboratory for the industrial-scale slaughter of the 20th century.

The Civil War served as a brutal laboratory for the industrial-scale slaughter of the 20th century.

This was the first "industrial war," utilizing mass-produced rifled muskets, railroads for troop movement, and the telegraph for real-time command. The introduction of ironclad warships and steamships revolutionized naval combat, while the use of trenches and rapid-fire weaponry foreshadowed the carnage of World War I. The lethality of these technologies, paired with Napoleonic-era tactics, resulted in 700,000 deaths—the deadliest conflict in American history.

The war's legacy remains a subject of intense cultural and historiographical debate, particularly regarding Reconstruction and the civil rights of the freed population. While the war settled the questions of slavery and secession, it left a "war-torn nation" to grapple with the complexities of reintegration. The myth of the "Lost Cause" persisted for over a century, attempting to romanticize the Confederate effort and obscure the brutal reality of the slavery that triggered the slaughter.

Image from Wikipedia

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln, an 1860 photograph portrait of Abraham Lincoln by Mathew Brady

Status of the states, 1861 Slave states that seceded before April 15, 1861 Slave states that seceded after April 15, 1861 Border Southern states that permitted slavery but did not secede (both KY and MO had dual competing Confederate and Unionist governments) Union states that banned slavery Territories

Division of the states during the American Civil War: Union Confederacy Border states Territories

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America (1861–1865)

The Battle of Fort Sumter, as depicted by Currier and Ives

US secession map, showing the Union and the Confederacy Union states Union territories not permitting slavery Southern Border Union states, permitting slavery (One of these states, West Virginia, was created in 1863, while KY, WV and MO had dual competing Confederate and Unionist governments) Confederate states Union territories that permitted slavery (claimed by Confederacy) at the start of the war, but where slavery was outlawed by the US in 1862

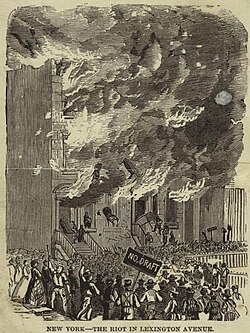

Rioters attacking a building during the New York anti-draft riots of 1863

Newton Knight, one of the founders of the Free State of Jones

Union soldier held as a POW

Susan B. Anthony was a women's rights activist and abolitionist.

Battle between the USS Monitor and Merrimack

General Scott's Anaconda Plan, featuring a tightening naval blockade, forcing rebels out of Missouri along the Mississippi River, Kentucky Unionists sit on the fence, idled cotton industry illustrated in Georgia.

Gunline of nine Union ironclads. South Atlantic Blockading Squadron off Charleston. Continuous blockade of all major ports was sustained by North's overwhelming war production.

A December 1861 cartoon in Punch magazine in London ridicules American aggressiveness in the Trent Affair. John Bull, at right, warns Uncle Sam, "You do what's right, my son, or I'll blow you out of the water."