Alan Turing

Turing defined the limits of what machines can "think" before a physical computer even existed.

Turing defined the limits of what machines can "think" before a physical computer even existed.

In 1936, Turing published a paper that is now considered the founding document of computer science. He introduced the "Turing machine," a theoretical model that could simulate any algorithmic process. By proving that some problems are "undecidable"—meaning no machine could ever solve them—he established the mathematical boundaries of computation.

This work was remarkably visionary because it decoupled the concept of a computer from the hardware. While his contemporaries were building machines for specific tasks, Turing’s "Universal Machine" proved that a single device could perform any task if provided with the right program. This remains the fundamental logic of every smartphone and laptop today.

His cryptanalysis at Bletchley Park provided the decisive intelligence edge that shortened World War II.

His cryptanalysis at Bletchley Park provided the decisive intelligence edge that shortened World War II.

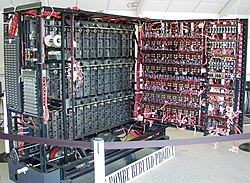

During the war, Turing led "Hut 8" at Bletchley Park, the unit responsible for breaking the German naval Enigma ciphers. He didn't just break codes manually; he engineered a solution. He developed the bomba, an electromechanical device that could scan through thousands of Enigma settings to find the key.

This work produced "Ultra" intelligence, which allowed the Allies to track U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic. Historians estimate that his team's work shortened the war by at least two years, saving millions of lives. Because his work was protected by the Official Secrets Act, his pivotal role in the Allied victory remained unknown to the public for decades.

The loss of his first love, Christopher Morcom, turned a grieving teenager toward the intersection of matter and spirit.

The loss of his first love, Christopher Morcom, turned a grieving teenager toward the intersection of matter and spirit.

At age 16, Turing formed a deep intellectual and emotional bond with a schoolmate named Christopher Morcom. When Morcom died suddenly of tuberculosis in 1930, Turing was devastated. He coped by obsessing over how a human "spirit" could survive the death of the physical body.

This trauma drove Turing’s interest in the "mechanism" of the mind. He spent years writing to Morcom’s mother, exploring the idea that the brain is a machine that "holds" a spirit. This search for a bridge between the physical and the metaphysical eventually evolved into his pioneering work on Artificial Intelligence and the question of whether a machine could ever truly possess a mind.

Beyond logic and code, Turing pioneered "Morphogenesis" to explain how life creates complex patterns.

Beyond logic and code, Turing pioneered "Morphogenesis" to explain how life creates complex patterns.

In his later years, Turing pivoted from computers to biology. He was fascinated by how a simple embryo develops into a complex organism with stripes, spots, or limbs. In 1952, he published "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis," proposing that biological patterns emerge from the interaction of two diffusing chemicals.

His mathematical models predicted oscillating chemical reactions that wouldn't actually be observed in a laboratory until the 1960s. This work laid the groundwork for modern mathematical biology, suggesting that the "chaos" of life is actually governed by elegant, predictable mathematical rules.

A state-sponsored tragedy ended his life, eventually sparking a national movement for retroactive justice.

A state-sponsored tragedy ended his life, eventually sparking a national movement for retroactive justice.

Despite his wartime heroism, Turing was prosecuted in 1952 for "gross indecency" due to his homosexuality. To avoid prison, he submitted to "chemical castration"—hormone injections designed to suppress his libido. Two years later, he died of cyanide poisoning at age 41; while officially ruled a suicide, some believe it may have been an accidental lab mishap.

The "appalling way" he was treated eventually led to a massive shift in British law. In 2013, he received a posthumous royal pardon from Queen Elizabeth II. This paved the way for the 2017 "Alan Turing Law," which retroactively pardoned thousands of other men convicted under historical anti-homosexuality legislation.

Image from Wikipedia

English Heritage blue plaque in Maida Vale, London marking Turing's birthplace in 1912

Turing at age 16, c. 1928 – c. 1929

Turing in the 1930s

King's College, Cambridge, where Turing was an undergraduate in 1931 and became a Fellow in 1935. The computer room is named after him.

Two cottages in the stable yard at Bletchley Park. Turing worked here in 1939 and 1940, before moving to Hut 8.

A working replica of a bombe now at The National Museum of Computing on Bletchley Park

Statue of Turing holding an Enigma machine by Stephen Kettle at Bletchley Park, commissioned by Sidney Frank, built from half a million pieces of Welsh slate

Plaque, 78 High Street, Hampton

A blue plaque commemorating Alan Turing's work at the University of Manchester where he was a Reader from 1948 to 1954

The Dancehouse Theatre, formerly the Regal Cinema, pictured in 2006, outside of which Turing met Arnold Murray

A blue plaque on the house at 43 Adlington Road, Wilmslow, where Turing lived and died

Turing's OBE currently held in Sherborne School archives