Aesthetics

Aesthetics is the "sensory logic" that evaluates everything from fine art to the natural world.

Aesthetics is the "sensory logic" that evaluates everything from fine art to the natural world.

While often used interchangeably with the "philosophy of art," aesthetics has a much broader reach. It examines the nature of beauty and taste wherever they occur—whether in a canvas, a sunset, or a well-designed tool. Philosophy of art is technically a subfield that focuses specifically on human-made artifacts, their meanings, and the intent of the creator. Aesthetics, however, is interested in the raw mechanics of "sensory value."

This field attempts to solve a fundamental riddle: why do certain things evoke a "wow" response? It categorizes aesthetic properties into values like beauty and ugliness, but also more nuanced qualities like grace, elegance, and vividness. These aren't just descriptions; they are the building blocks of how we rank our experiences of the world.

The central conflict pits "objective realism" against the subjective experience of the observer.

The central conflict pits "objective realism" against the subjective experience of the observer.

A major dividing line in aesthetics is whether beauty is a property of the object (like its weight or color) or a product of the human mind. Realists argue that aesthetic properties are "emergent"—for example, the beauty of a painting is an objective result of specific color and shape combinations. If everyone on Earth disappeared, the painting would still be "balanced" and "vivid" because those qualities are baked into its physical form.

Opposing this is the "response-dependent" view, which argues that beauty is purely in the eye of the beholder. This perspective, often rooted in phenomenology, suggests that the "aesthetic object" isn't the physical canvas itself, but the intentional object created in the viewer’s consciousness. Under this view, aesthetics is not a study of things, but a study of the interaction between things and minds.

True aesthetic engagement requires a "disinterested" state that ignores practical utility.

True aesthetic engagement requires a "disinterested" state that ignores practical utility.

A hallmark of aesthetic experience is the "aesthetic attitude," a specific mode of observation detached from personal desire or practical needs. To look at a storm aesthetically is to admire the pattern of the lightning and the roar of the wind without worrying about whether your roof will leak. It is a state of "selfless absorption" where you appreciate an object for its own sake rather than what it can do for you.

This "disinterested pleasure" is what separates an aesthetic experience from a practical or scientific one. While a scientist looks at a flower to understand its biology and a florist looks at it for its market value, the aesthetic observer looks at it simply for the "free play" it creates between their imagination and their understanding. Philosophers like Schopenhauer even suggested that this detached state allows us to perceive truths about reality that are usually obscured by our daily needs and biases.

While beauty focuses on harmony, the "Sublime" captures the power of awe and fear.

While beauty focuses on harmony, the "Sublime" captures the power of awe and fear.

For centuries, beauty was the only value that mattered in aesthetics, defined by the "classical conception" of harmony, proportion, and balance. It was seen as an objective arrangement of parts that created a coherent whole. However, as the field evolved, philosophers realized that some of our most profound experiences aren't "beautiful" in a traditional, pleasant sense.

This led to the rise of the "Sublime"—the appreciation of things that are vast, overwhelming, or even terrifying, such as a massive mountain range or a violent ocean. Unlike beauty, which provides comfort and pleasure, the sublime evokes awe and a sense of our own insignificance. Modern aesthetics now encompasses a massive spectrum of values, from the "refined" pleasure of a symphony to the "unrefined" visceral reaction to drama and tragedy.

The nature of aesthetic experiences, like the admiration of artworks, is a central topic of aesthetics.

Diagram of the relation between aesthetic concepts. Philosophers debate whether aesthetic objects are material or intentional objects.

In his 1790 book Critique of Judgment, Immanuel Kant argued that aesthetic judgments are subjective, universal, disinterested, and involve an interplay of sense, imagination, and understanding.

Conventionalist definitions of art assert that art is a socially constructed category. They explain that readymade objects like Marcel Duchamp's Fountain are considered art by reference to established conventions.

Some categorizations of art forms focus on the medium used to express artistic ideas, such as the use of oil paint.

The emotions artworks express are a central topic in the philosophy of art, such as the feelings of alienation and existential dread in Edvard Munch's 1893 painting The Scream.

Interpretation seeks to uncover the meaning of artworks, such as the significance of the canvas and mirror shown in Diego Velázquez's 1656 painting Las Meninas.

Dance is a performance art involving a series of bodily movements.

Architecture is an art that typically combines aesthetic with functional goals, such as Antoni Gaudí's Sagrada Família.

Evolutionary psychology examines the evolutionary function of aesthetic sensitivities, like preferences for environments conducive to survival, such as landscapes resembling the African savannah.

Chinese aesthetics places specific emphasis on poetry, painting, and calligraphy. They are known as the three perfections and are sometimes combined in a single artwork, as in Kun Can's Landscape after Night Rain Shower.

Religious art serves specific religious functions, such as conveying moral teachings or aiding devotional practices.

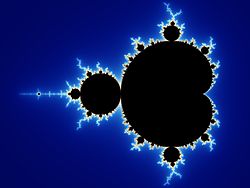

Computer art includes the generation of images using algorithms, such as the fractal geometry of the Mandelbrot set.

Plato understood art as a craft that imitates reality.

Artistic woodcut illustration of Al-Farabi, who envisioned beauty as a divine attribute of Allah