A Brief History of Time

Hawking bet on extreme accessibility by stripping away the math to reach the "airport bookshop" reader.

Hawking bet on extreme accessibility by stripping away the math to reach the "airport bookshop" reader.

While most physics texts rely on complex calculus, A Brief History of Time was engineered for the general public. Hawking’s editor famously warned him that every equation included would halve the book's readership. Consequently, the book contains only one: $E=mc^2$. This focus on non-technical metaphors rather than jargon helped the book sell over 25 million copies, proving there was a massive, untapped appetite for high-level cosmology.

The book doesn't just simplify; it humanizes science. Hawking weaves in anecdotes—from "turtles all the way down" to his famous bet with Kip Thorne over the existence of black holes—to ground abstract concepts. By framing the "fate of the universe" as a narrative rather than a set of data points, Hawking transformed a dense academic subject into a global cultural phenomenon.

The universe shifted from a static, eternal stage to a dynamic history born from a single, dense point.

The universe shifted from a static, eternal stage to a dynamic history born from a single, dense point.

For centuries, the prevailing "common sense" was that the universe was static and eternal. Hawking traces the disruption of this idea from Aristotle’s geocentric spheres to Edwin Hubble’s 1929 discovery that galaxies are moving away from us. Hubble’s observation of the "redshift" provided the first concrete evidence that the universe is expanding, implying it must have had a beginning—a singularity of infinite density.

This shift changed the role of time itself. In the Newtonian view, time was absolute and independent. In the post-Einsteinian view presented by Hawking, time is linked to space and matter. If the universe began 10 to 20 billion years ago, Hawking argues that asking "what happened before the beginning" is a meaningless question, as time itself did not exist to facilitate "before."

Modern physics rests on two foundational pillars that currently refuse to speak the same language.

Modern physics rests on two foundational pillars that currently refuse to speak the same language.

Hawking explains that our understanding of reality is split between General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics. Relativity is the "macro" theory; it describes gravity as the curvature of spacetime and works beautifully for stars and galaxies. Quantum Mechanics is the "micro" theory; it describes the subatomic world where the Uncertainty Principle reigns, making it impossible to know a particle's position and velocity simultaneously.

The tension between these two is the central conflict of the book. Relativity assumes a smooth, predictable universe, while Quantum Mechanics introduces an "irreducible element of unpredictability." Hawking explores the quest for a Unified Theory—a "theory of everything"—that can reconcile these two, particularly in extreme environments like black holes where the very large (gravity) meets the very small (singularities).

Reality is built from particles that follow a strict "no-sharing" policy and forces that may once have been one.

Reality is built from particles that follow a strict "no-sharing" policy and forces that may once have been one.

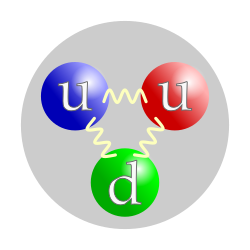

At the subatomic level, the universe is divided into two camps: fermions (matter) and bosons (force-carriers). Hawking details how fermions, like quarks and electrons, obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which prevents them from occupying the same state. This "no-sharing" rule is the only reason matter doesn't collapse into a dense blob, allowing for the existence of atoms and, eventually, people.

Beyond the particles, Hawking discusses the four fundamental forces: gravity, electromagnetism, and the weak and strong nuclear forces. A key insight of the book is that at extremely high temperatures—like those just after the Big Bang—these forces lose their distinctions and behave as a single, "grand unified" force. This suggests that the complexity we see today is just the "cooled-down" version of a much simpler, symmetrical origin.

Black holes are not just cosmic drains but complex regions where gravity and entropy collide.

Black holes are not just cosmic drains but complex regions where gravity and entropy collide.

Once considered a mathematical fluke, black holes are described by Hawking as the ultimate test of physical laws. He explains the life cycle of stars: when a massive star exhausts its fuel, it collapses. If it passes the "Chandrasekhar limit," nothing can stop it from shrinking into a black hole—a region where gravity is so strong that even light is trapped within the "event horizon."

However, Hawking’s most famous contribution (which he introduces toward the end) is the idea that black holes aren't "perfectly" black. By applying quantum mechanics to the edge of a black hole, he suggests they must emit radiation and possess entropy (disorder). This bridge between thermodynamics and gravity was a breakthrough, suggesting that black holes eventually evaporate, though the process takes longer than the current age of the universe.

Image from Wikipedia

Ptolemy's Earth-centric model about the location of the planets, stars, and Sun

The expansion of the universe since the Big Bang

Light interference causes many colours to appear.

A particle of spin 1 needs to be turned around all the way to look the same again, like this arrow.

A proton consists of three quarks, which are different colours due to colour confinement.

The Big Bang and the evolution of the universe

The fundamental objects of string theory are open and closed strings.